History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences

Podcast episode 34: Interview with Mary Laughren on Central Australia languages and Ken Hale

In this episode, we talk to Mary Laughren about research into the languages of Central Australia in the mid-twentieth century, with a focus on the contributions of American linguist Ken Hale.

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

References for Episode 34

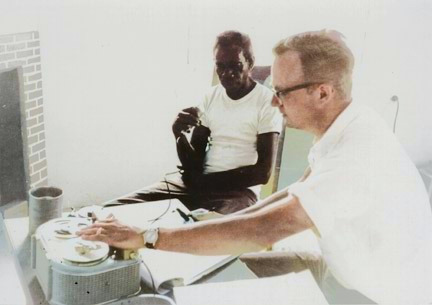

Hale, Kenneth L., and Kenny Wayne Jungarrayi. 1958. Warlpiri elicitation session. archive.org

Laughren, Mary, with Kenneth L. Hale, Jeannie Nungarrayi Egan, Marlurrku Paddy Patrick Jangala, Robert Hoogenraad, David Nash, and Jane Simpson. 2022. Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. Publisher’s website

Comparative historical reconstruction in Australian languages:

Hale, Kenneth L. 1962. Internal relationships in Arandic of Central Australia. In A. Capell Some linguistics types in Australia, 171-83. (Oceanic Linguistic Monograph 7), Sydney: Oceania (The University of Sydney).

Hale, Kenneth L. 1964. Claassification of Northern Paman languages, Cape York Peninsula, Australia: a research report. Oceanic Linguistics 3/2:248-64.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1976. Phonological developments in particular Northern Paman languages. In Peter Sutton, ed. Languages of Cape York, 7-40. Canberra: AIAS.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1976. Phonological develpments in a Northern Paman languages: Uradhi. In Peter Sutton, ed. Languages of Cape York, 41-50. Canberra: AIAS.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1976. Wik reflections of Middle Paman phonology. In Peter Sutton, ed. Languages of Cape York, 50-60. Canberra: AIAS.

Syntax of Australian languages

Hale, Kenneth L. 1973. Deep-surface canonical disparities in relation to analysis and change: an Australian example, 401-458 in Current Trends in Linguistics, ed. by A. Sebeok. The Hague: Mouton.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1975. Gaps in grammar and culture, 295-315 in Linguistics and Anthropology, in In Honor of C.F. Voegelin, ed. by M.D. Kinkade et al. Lisse: Peter de Ridder Press.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1976. The adjoined relative clause in Australia, 78-105 in Grammatical Categories in Australian Languages, ed. by R.M.W. Dixon. Canberra: A.I.A.S.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1981. Preliminary remarks on the grammar of part-whole relations in Warlpiri, pp. 333-344 in Studies in Pacific Languages & Cultures in honour of Bruce Biggs, ed. by Jim Hollyman & Andrew Pawley. Auckland: Linguistic Society of New Zealand.

Hale, Kenneth L. 1983. Warlpiri and the grammar of non-configurational languages. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 1.1(January/February):5-47.

Universal Grammar and Language diversity

Hale, Kenneth L. 1996. Universal Grammar and the root of Linguistic Diversity. In Bobaljik et al. (eds), 137-161. (Originally given as Edward Sapir Lecture at 1995 LSA Linguistic Institute, Albequerque, New Mexico.)

Students supervised by Hale with Doctoral Dissertations on Australian languages

Klokeid, Terry J. 1976. Topics in Lardil Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, M.I.T. Cambridge, Mass.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2002. Warlpiri: theoretical implications. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, M.I.T. Cambridge, Mass.

Levin, Beth Carol. 1983. On the Nature of Ergativity. 373pp. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, M.I.T. Chapter 4: ‘Warlpiri’, pp.137-214.

Nash, David G. 1980. Topics in Warlpiri Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, M.I.T. Cambridge, Mass.

Pensalfini, Robert. 1997. Jingulu grammar, dictionary, and texts. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, M.I.T. Cambridge, Mass.

Simpson, Jane Helen. 1983. Aspects of Warlpiri Morphology and Syntax. Doctoral dissertation. Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, M.I.T. Cambridge, Mass.

Students from other Universities influenced by Hale’s work on Warlpiri

Larson, Richard K. 1982. Restrictive modification: relative clauses and adverbs. Doctoral dissertation, Dept. of Linguistics, University of Madison, Wisconsin.

Lexicon Project & Native American language dissertations.

Fermino, Jessie Littledoe. 2000. An introduction to Wampanoag grammar. M.Sc. MIT.

LaVerne, M. Jeanne. 1978. Aspects of Hopi Grammar. PhD MI

Platero, Paul. 1978. Missing nouns phrases in Navajo. PhD MIT

White Eagle, Josephine Pearl . 1983. Teaching scientific inquiry and the Winnebago Indian language, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Harvard University. PhD.

Other references:

Bobaljik, Jonathan David, Rob Pensalfini and Luciana Storto. 1996. Papers on Language Endangerment and the Maintenance of Linguistic Diversity. (MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 28). Cambridge Mass.

Carnie, Andrew, Eloise Jelinek and Mary Ann Willie. 2000. (eds). Papers in Honor of Ken Hale: Working paper in Endangered and Less Familiar Languages 1. (MIT Working Papers in Linguistics). Cambridge Mass.

Simpson, Jane, David Nash, Mary Laughren, Peter Austin and Barry Alpher. (eds). 2001. Forty years on: Ken Hale and Australian languages.

Transcript by Luca Dinu

KH: The following are utterances in Warlpiri spoken by Kenny from Yuendumu. [00:09] Head. [00:10]

KWJ: Jurru, jurru. [00:12]

KH: He hit me in the head. [00:14]

KWJ: Jurruju pakarnu, jurruju pakarnu. [00:17]

KH: Did he hit you in the head? [00:18]

KWJ: Pakarnuju, pakarnuju. [00:19]

JMc: What you just heard was an excerpt from an elicitation session with the Warlpiri man Kenny Wayne Jungarrayi, speaking Warlpiri, recorded in 1959 by the American linguist Ken Hale. [00:34] I’m James McElvenny, and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences podcast, online at hiphilangsci.net. [00:43] There you can find links and references to all the literature we discuss. [00:46] In this episode, we embark on a series of interviews in the history of Australian linguistics by looking at the 20th century research into the Central Australian language Warlpiri, and in particular the role played in this research by the American linguist Ken Hale. [01:04] This topic is not only of great historical interest, but also currently quite newsworthy. [01:09] The Warlpiri Encyclopaedic Dictionary, started by Ken Hale and worked on over a period of over 60 years by him and his collaborators, both Warlpiri and non-Warlpiri, appeared just at the end of last year. [01:23] To tell us about all the research initiated by Ken Hale and continued by his students and other associates, we’re joined by Mary Laughren, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Queensland. [01:35] So Mary, to get us started, could you perhaps tell us how you got involved with Central Australian languages and Warlpiri in particular? [01:46]

ML: Well, I did my undergraduate studies in Australia at the University of Queensland but then went to France, and I did my postgraduate work at the University of Nice. [01:57] The subject of my dissertation was a Senufo language from the Côte d’Ivoire, [02:03] which would have been about 1973, [02:06] I think my doctoral dissertation was presented. And then I got information actually from my mother. She had seen an advertisement for five field linguists to go to the Northern Territory to support the very newly inaugurated bilingual education programs. [02:26] It didn’t say where you would be, apart from some place in the Northern Territory. I’d never visited, I didn’t know anything about it, but it sounded quite an adventure and interesting thing to do. [02:39] So I applied for one of those positions. [02:42] And in 1975, I came back from the Ivory Coast, Côte d’Ivoire, to Australia and went to the head office of the then Northern Territory Division of the Australian Department of Education. [02:55] So it was the Labor government under Whitlam, and particularly his education minister, Kim Beazley Sr., [03:03] who inaugurated these bilingual education programs in communities where people requested to have their own language used in the formal education programs. [03:15] So I found myself in Darwin, and there was a sort of an advisory committee had been set up to advise the government on bilingual education and how it was progressing and how to go about it, etc. [03:30] It just happened that very shortly after my arrival in Darwin, [03:34] there was one of these meetings of this committee, and a linguist, Darrell Tryon, had visited Yuendumu on his way to the meeting and had been very heavily lobbied by Warlpiri people there that they really needed a linguist. [03:48] So I just happened to be this spare linguist that was sitting around Darwin. [03:53] And that’s really how I was sort of sent to Yuendumu, which I liked the idea of a lot, because I didn’t particularly want to be in the sultry tropics, [04:04] and I quite liked the idea of being in a desert community. [04:10]

JMc: On a day-to-day basis, what was it that you actually did as a linguist in the community? [04:14]

ML: Well, it really depended on what state the linguistic documentation was at and some of the linguists who had similar positions in other places. I mean, their job really was to do sort of really basic research on the language and to devise a writing system. [04:31] Now, fortunately, Ken Hale and other linguists had worked on Warlpiri before me and certainly, you know, Ken’s fantastic work, [04:40] and there was already a practical orthography, and there were already materials being produced to use in school programs. [04:51] So I was sort of ahead of the curve. [04:53] So what I really did, apart from trying to learn the language as best I could, [04:59] was work with young Warlpiri people. Both assistant teachers and special positions had been set up for people as literacy workers, I think they were called, to help produce these materials. [05:13] So they were often recording stories from other people in the community, [05:19] but then writing them down. [05:20] So these were people who were really quite literate in Warlpiri or various degrees of ability, of course. [05:28] And so I worked very carefully with them and also with the teachers to see what they thought was going to be helpful in the classroom, [05:36] and we sort of tried to produce materials and look at the whole range of education that you could do [05:43] in both Warlpiri and English, so whether it was mathematics or the natural sciences, as well as initial literacy. [05:50] It has to be said that this was 1975 when I went to Yuendumu, arrived in Yuendumu. [05:56] The school, I think, had only been set up about 1950. [05:59] In fact, the settlement was the same age as me. [06:02] It was created in 1946. [06:03] So, you know, formal schooling was really, you know, incredibly new. [06:09] And we’re talking about very, very impoverished communities. [06:14] I mean, I had come from West Africa, and I just couldn’t believe the standard of living of Warlpiri people, you know, or people throughout Central Australia in particular. [06:26] I’d never seen, you know, such poverty, such, you know, terrible living conditions. [06:31] You can imagine that formal schooling, in a way, didn’t have a lot of sort of relevance, in some ways, for people’s way of life, which was really a struggle to survive in many ways. [06:45] But before I came to Yuendumu, when I was still hovering around the office in Darwin, another linguist, Velma Leeding, [06:55] who had formerly worked for the Summer Institute of Linguistics but had then become a departmental linguist working on Groote Eylandt in particular, [07:05] She came to me and she said, “Oh, if you’re going to Yuendumu, you need to write to this professor, Ken Hale,” [07:13] which I wisely took her advice, looking back on it. [07:16] And I did, just to say, you know, “Here I am, this random person going to Yuendumu, and, you know, I’ve been advised to write to you,” and he wrote back. [07:26] And that’s how we started sort of a correspondence. [07:30] In those days, of course, there was no email or anything like that. [07:33] So, you know, written correspondence. [07:36]

JMc: Okay. So literacy had a function too in connecting linguists. [07:40]

ML: It had a function in connecting linguists. That’s right. [07:43] Absolutely. [07:44] And one of the fantastic bodies of materials that I found in Yuendumu was a photocopy of Ken’s field notes from his 1966-’67 field trip to Australia. [08:00] and where he did a lot of work, really in-depth work on Warlpiri with a number of Warlpiri men from different regions, [08:06] so covering different varieties or dialects of Warlpiri. [08:11] And when I found these, I started reading through them and working besides other Warlpiri speakers, including elderly people [08:24] who came in who were just interested in, you know, having a chat and stuff. [08:29] And so I was able to ask where I didn’t understand things, I wasn’t sure of things or whatever. [08:36] And that was a really good way of getting into Warlpiri and learning more about Warlpiri. [08:42] And it’s really his collection from ’66, ’67, and the earlier work he did [08:50] with people like Kenny Jungarrayi Wayne in 1959, ’60, that have really… plus some other materials of his, and as well as a lot of other material as well. [09:02] But his material, in a way, is really the core of the information in the Warlpiri dictionary. [09:09]

JMc: OK. So his first trip to Warlpiri country was in ’59–’60. [09:13] Is that correct? [09:14] Ken Hale’s first trip was in ’59–’60. [09:17]

LM: Yeah, Ken Hale’s first trip to Australia, I think, was in, yeah, ’59–’60. [09:22] So he had a grant. [09:25] He was at the University of Indiana where he had done his PhD, and he got a grant to come out to Australia, [09:33] I think very much encouraged by the Voegelins. [09:36] Carl Voegelin had been his supervisor, [09:39] and wife Florence was there, and he was encouraged to come to Australia and got this grant, sort of arrived in Sydney and went and met Elkin at the University of Sydney and Arthur Capell, and Arthur Capell was very excited about his coming here. [09:59] Arthur Capell was really a linguist and often called the father of Australian linguistics [10:05] Elkin was, I think, less welcoming. [10:08] There was this sort of idea that different people sort of, you know, had exclusive right to different languages, and really wherever Ken thought that he might go, he was sort of blocked, in a way. [10:20] But in the end, he said, “Well, let’s just… We know that people in Alice Springs speak Aboriginal languages,” [10:26] so he went to Alice Springs and started working [10:30] with people on the Arandic languages, which to my mind are incredibly difficult languages to work on. [10:38] But in almost no time at all, he had gone round to various communities out from Alice Springs and really did some very exciting documentation of different varieties of Arrernte and also was able to see the connection. [10:54] So one of his first interests, I guess, was really historical-comparative work. [10:59] And he did, you know, really interesting work on the relationships between these various varieties of Arrernte. [11:06] But then he met Warlpiri people, of course, the Warlpiri people living in the area of Alice Springs, within Alice Springs. [11:15] And so he started working on Warlpiri at that time as well. [11:19]

JMc: And can you just fill us in, [11:20] what is the genetic relationship like between Warlpiri, Arandic languages and Luritja? [11:26]

ML: They’re all Pama–Nyungan languages, but they belong really to different sub-families, if you like, of the Pama–Nyungan group. [11:33] So you’ve got the Arandic languages, and Warlpiri is really part of a Yapa, Ngumpin–Yapa group. [11:41] related with languages further west and further to the north. [11:45] Warlpiri is the most southern of that group of languages. [11:48] And then Luritja, to the south of Warlpiri, is one of the Western Desert languages. [11:53] Of course, the Western Desert languages are spread over a very, very large area of Australia, into Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. [12:01]

JMc: Now, you mentioned that the documentation that Ken Hale produced became the heart of the Warlpiri Dictionary, [12:08] but could you say a little bit more also about his other connections to the community? [12:13] Was he involved in these 1970s efforts to boost bilingual education, for example? [12:19] And did he have other connections to the community itself? [12:23]

ML: Yeah, very much so. [12:25] So he had spent time in Yuendumu, and [12:29] he was asked by the government before these programs were actually officially introduced — so very soon after the Whitlam government got power — [12:40] he and Geoff O’Grady, with whom he had worked and done a very large field trip in 1960, they were asked to write a report for the government about the feasibility of bilingual education and also how it might be implemented, [12:58] which he did. [12:59] So that was actually very, very influential, and they made quite a number of recommendations, very concrete recommendations. [13:07] And I know that that was held as sort of a blueprint really by the NT division of the department, which had the job of implementing these programs. [13:17] So when Yuendumu school got the go-ahead to start doing bilingual education, the local store, which was called the Yuendumu Social Club, raised the money to bring Ken Hale out, and he prepared a number of really useful materials: a syllabary, a basic, what he called an elementary dictionary of Warlpiri. [13:38] He gave classes to a whole lot of young adults who had had some schooling in Warlpiri writing system, etc. [13:48] So that’s why when I arrived in ’75, there were all these people who were quite adept at writing Warlpiri, which was fantastic. [13:55] So, yes, he did things like that. [13:58] And he went to the various Warlpiri communities sort of running these little courses, [14:03] and people were still speaking about that experience, you know, many, many, many years later [14:09] and how they enjoyed that and what they’d got out of it. [14:13] And just when I went back to Yuendumu in March for the launch of the Warlpiri dictionary, a man came up to me and he said, “Yes, I remember Ken Hale.” [14:24]

JMc: So what would you say were Ken Hale’s main contributions to the development of linguistics? [14:30] Was he mainly a data collector, or was he also a theorist? [14:34]

ML: Well, he was both: his ability to record and to learn languages, and to hear the fine phonetic detail, to work out the phonology of a language. [14:50] And I think some of the languages that he worked on in his first trip, like the Arandic languages and [14:56] languages in North Queensland that have had lots of phonological changes historically compared to more conservative languages like Warlpiri and the Western Desert languages and many others is really quite phenomenal, really, to have that sort of ability. [15:12] So he had that extraordinary ability, and he had sort of worked out a method of initial elicitation, which was not only to get words and basic morphology, certainly to get that, [15:26] but also other, he was interested also in grammar, in syntax. [15:30] So he had a very, very sort of interesting way of proceeding with his elicitations. [15:37] And because he was so good, in very, very short amounts of time, he was able to collect an enormous amount of data, and data which is very reliable, you know, phonetically reliable, phonologically reliable, morphologically and all the rest of it. [15:51] So he… [15:52] Even though he may not have worked, done further work on lots of the languages from which he collected data, other people have certainly been able to work on that language, and you’ll often find in dictionaries and grammars and all sorts of things [16:09] an acknowledgement that a lot of the basic materials actually come from Ken Hale’s field notes, as well as having the best of the training an American university could give at that time in linguistics and linguistic theory, methodology. [16:25] He also had a background in anthropology, [16:28] and that really comes through in his understanding, for example, of the complex kinship systems and kinship terminology, particularly thinking of the Warlpiri tri-relational kinship terms, the way in which even the grammatical parts of a language are manipulated in respect speech registers, etc., is really incredibly good. [16:52] But he was also very, very interested in modern theories of linguistics. [17:00] I think just his knowledge of so many languages, he could appreciate the diversity that you get in languages, but also the sameness that you get. [17:12] Anybody that works on a lot of languages, you keep coming back to the same things, the certain sort of constraints about a system that’s learnable by human beings. [17:22] And I think he contributed quite a lot through his work, [17:27] for example his work on non-configurational languages, looking at languages like Warlpiri with their relatively free word order or phrasal order. [17:38] His work on the Lexicon Project, for example, which he set up with Jay Keyser at MIT in the 1980s, I think was very influential. [17:48]

JMc: There’s some key words there, “a system of constraints learnable by humans,” and even the name of the institution, MIT. [17:57] So Ken Hale was, of course, a professor at MIT, [18:01] and that’s the home of generative linguistics. [18:04] And generative linguists are often characterized or perhaps caricatured as being interested only in inventing new theoretical devices on the very thin empirical basis of their intuitions of English, maybe with a few other major European languages in the mix. [18:20] So how did Ken Hale, who was a confirmed field linguist, fit into this scene at MIT? [18:27] Did the data that he brought back from the field feed into the further development of theory, [18:32] and is it inaccurate to say that MIT linguists are not interested in typological diversity and empirical data on the languages of the world? [18:44]

ML: Yeah, I think that idea that MIT people are only there [18:50] inventing theories out of some work on English is completely ridiculous. [18:56] It’s just completely wrong. [18:58] I spent quite an amount of time at MIT working with Ken in the 1980s and followed the work of various people and graduate students working on a whole range of languages, from American Indian languages to Asian languages, [19:16] a variety of European languages, languages from all over, including Australian languages. [19:21] So Australian PhD students like David Nash, Jane Simpson, and American students like Julie Anne Legate, for example, worked on Warlpiri with Ken, people working on Leerdil and other Australian languages. [19:34] But yeah, at MIT people were interested in languages generally, you know, and were looking at the similarities and differences across a whole range of languages. [19:45] I mean, I met students from China, from Japan. [19:48] So I think that’s just a ridiculous, as you said, it’s a sort of a caricature, and I think it’s got no evidential basis whatsoever. [19:57] So, Ken actually didn’t go to MIT till after his second field trip to Australia when he was invited by Morris Halle to join the department there. [20:06] So his initial work was really out of University of Indiana. [20:10]

JMc: OK. And why did Morris Halle want Ken Hale at MIT? [20:16]

ML: Because he’d heard about this very brilliant linguist, and he wanted the best at MIT, [20:23] and so he invited Ken to consider joining the department. [20:30] Ken Hale once said to me that… Actually, he wrote a really interesting paper and he gave it as the Edward Sapir Lecture at the American Linguistic Institute in 1995, [20:42] and I think it’s called something like “Universal Grammar and the Roots of Linguistic Diversity.” [20:48] That paper sort of… I reread it today, and it reminded me of something he once said that you could look at any one language, and you could probably find out most of what there was to be found out about human language. [20:59] Right? [21:01] If you go deep enough into the language. [21:04] But of course, some languages are much more overt in some of the characteristics of human language than others, right? [21:10] So there’s much more sort of surface evidence there for certain characteristics. [21:16] And I personally think that that’s probably very, very true. [21:20] But by looking at a diversity of languages, you can both confirm hypotheses, clearly [21:26] — so one often finds things that are just so similar across languages, even though on the surface they look to be very different; they’re certainly not related historically — [21:38] and the other thing about the diversity, of course, you can find counterexamples. [21:42] So to any theory, you know, [21:43] if it’s not something that you can find some counter-evidence for, [21:46] I mean, the theory, of course, is not tenable. [21:49] So, you know, that’s part of his interest was really both confirming and disconfirming, if you like. [21:55] And I think the work that he did on bringing to prominence languages with very free word order, and not just Warlpiri, but other languages from around the world that had much more freedom of word order, apparently, than English, [22:09] I think led to all sorts of very interesting work that was done on languages by linguists from all over. [22:17]

JMc: You mentioned that word order in Warlpiri is a lot freer than in a language like English, for example, [22:23] and I believe one of the parameters of universal grammar that Ken Hale proposed was this non-configurationality parameter. [22:32]

ML: Well, I think the w*, that you could put things in any order – although, of course, [22:39] Ken knew very well that even in Warlpiri, there were certain ordering constraints. [22:44] And I think his idea, sort of throwing out these ideas, other people sort of took them up and also looked for explanations for, why are there languages that are like that and languages that aren’t like that, [22:57] and what is the real difference between them? [23:00] How do we characterize one language as opposed to another? [23:04] Where do these differences spring from? [23:08] And various people have come up with various proposals, etc. [23:12] So I think that was really Ken’s sort of ideas, which came out of his fieldwork, but also out of very deep reflection about language and on the basis of knowing lots of different languages very well, was really to throw out ideas, to throw out sometimes sort of initial explanations or characterizations of the problem, if you like, for linguists to solve, for other people to really get their teeth into. [23:41] And I think it was very similar with his work in the Lexicon Project, where he was really interested in that relationship between semantics and syntax, [23:50] where the certain types of meaning, or the explanation of meaning, sort of constrained the syntax and the relationship between levels of languages. [23:59] And that really spawned a lot of really great work by a whole lot of people addressing this question of this interaction between syntax and semantics, [24:09] what constrains what. [24:11]

JMc: OK, excellent. Well, thank you very much for answering those questions. [24:16]

ML: My pleasure. [24:20]

JMc: We’ll close now with an excerpt from a recording of a Warlpiri song sung to the melody of “Freight Train”. [24:27] The Warlpiri lyrics are by Ken Hale, and this performance of the song is by Warlpiri teachers in Yuendumu in 2009. [24:35] Wendy Baarda is accompanying them on guitar. [24:37] [music] [24:41]

Singers: [singing in Warlpiri] [24:54]