- Affärsnyheter

- Alternativ hälsa

- Amerikansk fotboll

- Andlighet

- Animering och manga

- Astronomi

- Barn och familj

- Baseball

- Basket

- Berättelser för barn

- Böcker

- Brottning

- Buddhism

- Dagliga nyheter

- Dans och teater

- Design

- Djur

- Dokumentär

- Drama

- Efterprogram

- Entreprenörskap

- Fantasysporter

- Filmhistoria

- Filmintervjuer

- Filmrecensioner

- Filosofi

- Flyg

- Föräldraskap

- Fordon

- Fotboll

- Fritid

- Fysik

- Geovetenskap

- Golf

- Hälsa och motion

- Hantverk

- Hinduism

- Historia

- Hobbies

- Hockey

- Hus och trädgård

- Ideell

- Improvisering

- Investering

- Islam

- Judendom

- Karriär

- Kemi

- Komedi

- Komedifiktion

- Komediintervjuer

- Konst

- Kristendom

- Kurser

- Ledarskap

- Life Science

- Löpning

- Marknadsföring

- Mat

- Matematik

- Medicin

- Mental hälsa

- Mode och skönhet

- Motion

- Musik

- Musikhistoria

- Musikintervjuer

- Musikkommentarer

- Näringslära

- Näringsliv

- Natur

- Naturvetenskap

- Nyheter

- Nyhetskommentarer

- Personliga dagböcker

- Platser och resor

- Poddar

- Politik

- Relationer

- Religion

- Religion och spiritualitet

- Rugby

- Så gör man

- Sällskapsspel

- Samhälle och kultur

- Samhällsvetenskap

- Science fiction

- Sexualitet

- Simning

- Självhjälp

- Skönlitteratur

- Spel

- Sport

- Sportnyheter

- Språkkurs

- Stat och kommun

- Ståupp

- Tekniknyheter

- Teknologi

- Tennis

- TV och film

- TV-recensioner

- Underhållningsnyheter

- Utbildning

- Utbildning för barn

- Verkliga brott

- Vetenskap

- Vildmarken

- Visuell konst

SDG

A podcast about the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 17 goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015.

77 avsnitt • Längd: 0 min • Månadsvis

Om podden

A podcast about the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 17 goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015.

The podcast SDG is created by Dom Billings. The podcast and the artwork on this page are embedded on this page using the public podcast feed (RSS).

Avsnitt

SDG Target #17.19

SDG #17 is to “Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development”

Within SDG #17 are 19 targets, of which we here focus on Target 17.19:

By 2030, build on existing initiatives to develop measurements of progress on sustainable development that complement gross domestic product, and support statistical capacity-building in developing countries

Target 17.19 has two indicators:

Indicator 17.19.1: Dollar value of all resources made available to strengthen statistical capacity in developing countries

Indicator 17.19.2: Proportion of countries that (a) have conducted at least one population and housing census in the last 10 years; and (b) have achieved 100 per cent birth registration and 80 per cent death registration

This target highlights the work of PARIS21. This organisation works to help developing countries increase their statistical capacity.

The developing countries which had the most dollars available for statistical capacity were in Africa. Vietnam, Serbia, and Nepal also each spent over $10 million to this end in 2020. Global spending on increasing statistical capacity in 2020 was $541 million.

As of 2017, only a dozen countries hadn’t completed a census in the past decade. The country with the smallest proportion of registered births was in the Horn of Africa. In Ethiopia and Somalia, the rate was less than 6%. The global rate of birth registrations was 72% of births as of 2018. Several African countries and Afghanistan registered deaths at a rate lower than 10%.

SDG Target #8a

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.a:

Increase Aid for Trade support for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, including through the Enhanced Integrated Framework for Trade-related Technical Assistance to Least Developed Countries

Target 8.a has one indicator:

Indicator 8.a.1: Aid for Trade commitments and disbursements

Aid for Trade is an initiative of the World Trade Organization for high-income donor countries to help developing countries to trade to further their economic development.

An example of aid which might help towards this end is infrastructure, such as transport networks and utilities, which all enable economic activity.

For the high-income OECD countries which give development assistance, in reporting what they’ve given, we can also separate what they’ve given as intended for Aid for Trade. Based on this, the developing regions as a whole received $52.5 billion as Aid for Trade in 2021. This figure has gone up and down in the years since the adoption of the Goals in 2015, when it was $62 billion. For the least developed countries, 2021 Aid for Trade commitments were $18.8 billion. This has also varied year-on-year since 2015, when it was $19.8 billion. On sum, this trend has been missing Target 8.a’s aim to increase Aid for Trade support.

On the donor side, the largest 2021 commitments earmarked for Air for Trade came from Germany, giving $7.3 billion, and Japan, with $6.8 billion.

SDG Target #8.10

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.10:

Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance and financial services for all

Target 8.10 has two indicators:

Indicator 8.10.1: (a) Number of commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults and (b) Number of automated teller machines (ATMs) per 100,000 adults

Indicator 8.10.2: Proportion of adults (15 years and older) with an account at a bank or other financial institution or with a mobile-money-service provider

One aspect of social inclusion is financial inclusion. This has become much more accessible with the proliferation of digital payment platforms to give access.

Worldwide, the number of commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults was 11.2 as of 2021, about the same as 2015. For the same year, there were 39 ATMs per 100,000 people worldwide, a small increase from 36 in 2015.

The proportion of adults with a bank account or similar in 2021 was 76%, an increase since the Goals adoption of 62%.

SDG Target #8.9

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.9:

By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

Target 8.9 has one indicator:

Indicator 8.9.1: Tourism direct GDP as a proportion of total GDP and in growth rate

This target introduces us to the work of another of the UN agencies, UN Tourism.

Tourism direct GDP, as measured in this Target’s sole indicator is the value-added by all industries contributing to tourism.

The global share of tourism direct GDP as a proportion of gross world product is 2.54% as of 2021. This is lower than at the adoption of the SDGs in 2015, when it was 3.75%.

The world leaders among countries with data in the SDG period are Fiji with 12% in 2019. For those with more recent data up to 2021, the leaders were Greece and UAE with 6%.

SDG Target #8.8

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.8:

Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment

Target 8.8 has two indicators:

Indicator 8.8.1: Fatal and non-fatal occupational injuries per 100,000 workers, by sex and migrant status

Indicator 8.8.2: Level of national compliance with labour rights (freedom of association and collective bargaining) based on International Labour Organization (ILO) textual sources and national legislation, by sex and migrant status

This target gets us a little closer to understanding what SDG #8 means by “decent work.” We can measure decent work, like we can with all topics covered in the SDG targets and indicators. We need work to be decent to achieve the other Goals relating to poverty reduction and to fulfil the equality aspirations of the SDGs. For all work to be safe and secure helps to further this aim.

In an earlier instalment in this series, we explored two treaties which put the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into effect. Article 22 of one of these, the ICCPR, enshrines freedom of association into international law by its parties:

“Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests.”

Some of the International Labour Organization conventions which guide international labour law include:

Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention of 1948

Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention of 1949

Equal Remuneration Convention of 1951

Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention of 1958

Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention of 1975

Domestic Workers Convention of 2011

Relevant human rights instruments adopted by the UN General Assembly include:

Also relevant are two protocols supplementing a UN convention against Transnational Organized Crime:

Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children of 2000

Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air

Many of the countries which may have been at highest risk of fatal occupational injuries don’t have data as of 2021. Though among those who do, the highest is Egypt, with 10 per 100,000 workers. For non-fatal occupational injuries, the highest is Costa Rica, with 9421 per 100,000 workers.

When measuring level of national compliance with labour rights, the world has scored 4.5 out of 0-10 measure, with 0 being the best. The worst performers as of 2021 were Iran and UAE with a score of 10, followed by China, scoring 9.

SDG Target #8.7

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.6:

Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms

Target 8.7 has one indicator:

Indicator 8.7.1: Proportion and number of children aged 5–17 years engaged in child labour, by sex and age

First, at the time of writing, we’re six months shy of 2025, and haven’t ended child labour in all its forms, so this aspect of this target is already foregone.

This target encapsulates the work of several UN labour and human rights agreements protecting the welfare of children:

International Labour Standards, overseen by the International Labour Organization

Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1989

Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict, adopted by the General Assembly in 1974

ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work

Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, adopted in 1956

Slavery Convention, adopted in 1926

As of 2020, UNICEF estimated 160 million children worldwide were in child labour, with an 8.4 million increase in the preceding four years.

The countries with the highest rates of child labour among those with data as of 2022 were Chad with 31% and Togo with 33%. Disaggregated by sex, in Togo, more boys were in child labour than girls by 3%, and in Chad, the gender difference was 6%. The biggest gender gap among countries with 2022 data was Senegal, with 8% of girls in labour and a quarter of boys.

SDG Target #8.6

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.6:

By 2020, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training

Target 8.6 has one indicator:

Indicator 8.6.1: Proportion of youth (aged 15–24 years) not in education, employment or training

There aren’t yet any global figures for the proportion of youth not in education, employment, or training. Of those countries with data for this indicator, Niger and Afghanistan are the worst-performing, with 68% and 62%. Rather than the proportion reducing, in both countries it’s rise since 2014: in Niger from 25% and Afghanistan from 35%. The Netherlands is the leader with 2%, having reduced from 4.7% in 2014.

SDG Target #8.5

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.5:

By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value

Target 8.5 has two indicators:

Indicator 8.5.1: Average hourly earnings of employees, by sex, age, occupation and persons with disabilities

Indicator 8.5.2: Unemployment rate, by sex, age and persons with disabilities

Only a couple dozen countries have data for employees’ average hourly earnings. The highest among them was Switzerland. By sex, the greatest difference was in South Korea, where the average hourly earnings of male employees of $23.96 and $15.91 for women.

The global unemployment rate as of 2022 was 5.3%, with gender differences only a fractional difference.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #8.4

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.4:

Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production, with developed countries taking the lead

Target 8.4 has two indicators:

Indicator 8.4.1: Material Footprint, material footprint per capita, and material footprint per GDP

Indicator 8.4.2: Domestic material consumption, domestic material consumption per capita, and domestic material consumption per GDP

Material footprint is a measure of the tonnage of natural resources extracted from the Earth. This includes metal ores, fossil fuels, minerals or living matter from plants and animals. Many of these are finite and non-renewable resources.

By contrast, the concept of domestic material consumption is a measure of materials used within a country’s economy.

It’s important we understand that the economy, which is the basis upon which we all prosper, itself rests upon an environment foundation. This begs the question how is the environment to cope as we live on a planet with a spiking increase in resource use? What is the pathway out of this pattern, to unlink economic growth from scarce resource use and extraction?

The world’s material footprint per capita was 12.44t as of 2019, the same figure as 2015. Thus, there has been no improvement on this indicator, as the target has asked of us. Indicator 8.4.1 asked us to measure by GDP as well as per capita. The world’s material footprint in 2019 was 1.14kg per US dollar, with not much of a change since 2015.

The domestic material consumption per capita for the world was 12 tonnes as of 2019, about the same since 2015. The target asked for developed countries to take the lead. As a proxy, we can use Europe and Northern America. This region had 18t of domestic material consumption in 2019, which has also remained the same since the start of the SDGs.

The global domestic material consumption is equal to 1.13kg per dollar. Once more, this is little changed from 2015, with a similar trend for Europe and Northern America.

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #8.3

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.3:

Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services

Target 8.3 has one indicator:

Indicator 8.3.1: Proportion of informal employment in total employment, by sector and sex

Of the countries with data, many of the Least Developed Countries had greater than 80% of workers in non-agricultural informal work. The numbers are also high in the very populous countries India and Bangladesh, with 80% and 91% of workers in the informal sector.

Much fewer countries have data for informal employment in the agriculture sector. This includes many of the countries with highest proportions of informality in non-agriculture. Developing countries with 2022 data had between 80-100% informal employment in agriculture.

The country with the greatest gender imbalance in the non-agricultural sector was Cote d'Ivoire. There, 79% of men were in informal employment and 93% of females. In agriculture, the biggest gender disparities among countries with data were in Europe. 31% of Serbian males compared to 68% of women were in informal employment, and 42% of males and 78% of women in Poland.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #8.2

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.1:

Sustain per capita economic growth in accordance with national circumstances and, in particular, at least 7 per cent gross domestic product growth per annum in the least developed countries

Target 8.1 has one indicator:

Indicator 8.1.1: Annual growth rate of real GDP per capita

This target and indicator ask for us to aim for an increase of GDP, but also to keep pace with price rises from inflation, but also population growth. If GDP rises 7%, but so does the population growth, the actual rise in GDP cancels out. Likewise, if the GDP rises 7% but the inflation rate is 4%, then the GDP growth is only 3%.

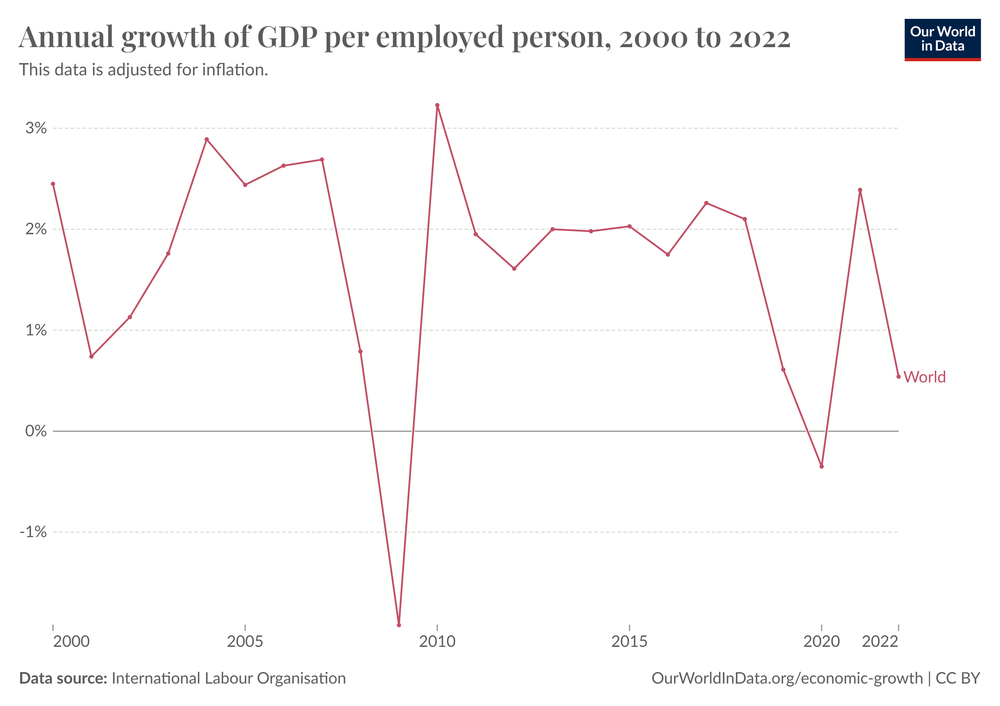

The per capita annual growth rate for the world economy in 2022 was 2.28%, an increase from 1.86% in 2015, the year of the SDGs adoption. In the years following 2015, there was a dip in 2016 to 1.60%, followed by an increase in 2017, a tiny dip in 2018, a drop in 2019 to 1.51%, then a big drop in 2020 to -4.03%. 2021 saw a 5.31% rise, before an almost halving in 2022.

In 2022, the only Least Developed Countries with GDP growth rates above 7% was Niger with 7.43%

SDG Target #8.1

SDG #8 is to “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.”

Within SDG #8 are 12 targets, of which we here focus on Target 8.1:

Sustain per capita economic growth in accordance with national circumstances and, in particular, at least 7 per cent gross domestic product growth per annum in the least developed countries

Target 8.1 has one indicator:

Indicator 8.1.1: Annual growth rate of real GDP per capita

This target and indicator ask for us to aim for an increase of GDP, but also to keep pace with price rises from inflation, but also population growth. If GDP rises 7%, but so does the population growth, the actual rise in GDP cancels out. Likewise, if the GDP rises 7% but the inflation rate is 4%, then the GDP growth is only 3%.

The per capita annual growth rate for the world economy in 2022 was 2.28%, an increase from 1.86% in 2015, the year of the SDGs adoption. In the years following 2015, there was a dip in 2016 to 1.60%, followed by an increase in 2017, a tiny dip in 2018, a drop in 2019 to 1.51%, then a big drop in 2020 to -4.03%. 2021 saw a 5.31% rise, before an almost halving in 2022.

In 2022, the only Least Developed Countries with GDP growth rates above 7% was Niger with 7.43%

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #7.b

SDG #7 is to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Within SDG #7 are 5 targets, of which we here focus on Target 7.b:

By 2030, expand infrastructure and upgrade technology for supplying modern and sustainable energy services for all in developing countries, in particular least developed countries, small island developing States and landlocked developing countries, in accordance with their respective programmes of support

Target 7.b has one indicator:

Indicator 7.b.1: Installed renewable energy-generating capacity in developing and developed countries (in watts per capita)

The least developed countries face the prospects of the largest growth in population in the years to come. The existing dearth of energy for these countries takes on a double importance for their eventual access to be renewable. What if it's not, and such energy access comes from fossil fuels? The fight against climate change would be all but lost to accommodate the increase in living standards. This isn’t fair, to deprive such developing countries from access, thus its vital access comes via renewable energy

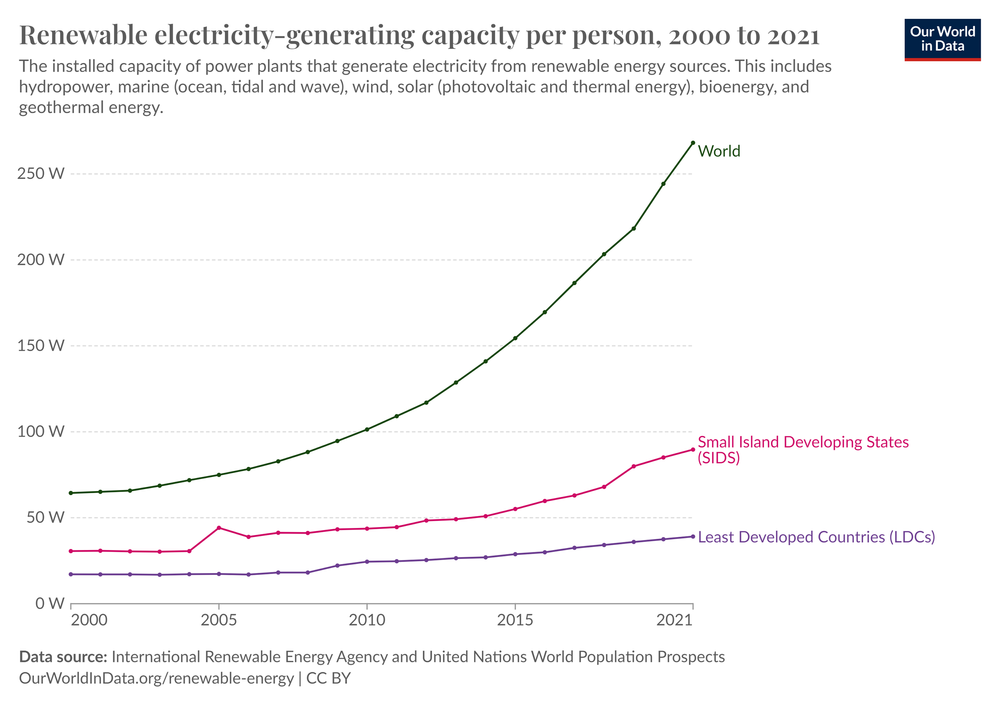

Th global capacity of renewable energy as of 2021 was 268 watts per capita, an increase from 154 watts per capita in 2015. In the Least Developed Countries in 2021, it was 39 watts per capita, up from 28 watts in 2015. In the Small Island Developing States, renewable energy capacity was 89 watts per capita in 2021, up from 55 watts in 2015.

SDG Target #7.a

SDG #7 is to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Within SDG #7 are 5 targets, of which we here focus on Target 7.a:

By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology

Target 7.a has one indicator:

Indicator 7.a.1: International financial flows to developing countries in support of clean energy research and development and renewable energy production, including in hybrid systems

The International Renewable Energy Agency tracks financing of aid for renewable energy.

In 2021, OECD country donors gave $10 billion as foreign aid intended for clean energy. Not only is this amount down from the 2017 peak of $27 billion, it’s also a decrease from the 2015 amount of $12 billion. It’s thus not on track to “enhance international cooperation” in the form of aid for renewable energy, as this target asks of us.

SDG Target #7.3

SDG #7 is to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Within SDG #7 are 5 targets, of which we here focus on Target 7.3:

By 2030, double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency

Target 7.3 has one indicator:

Indicator 7.3.1: Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP

The global energy intensity in 2020 was $4.54 of economic value produced per megajoule of energy used. This was down a little from the figure at the adoption of the SDGs in 2015 of $4.83 per megajoule. But it's still far from the doubling of improvement required for this target, which would be a halving of the energy intensity.

SDG Target #7.2

SDG #7 is to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Within SDG #7 are 5 targets, of which we here focus on Target 7.2:

By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services

Target 7.2 has one indicator:

Indicator 7.2.1: Renewable energy share in the total final energy consumption

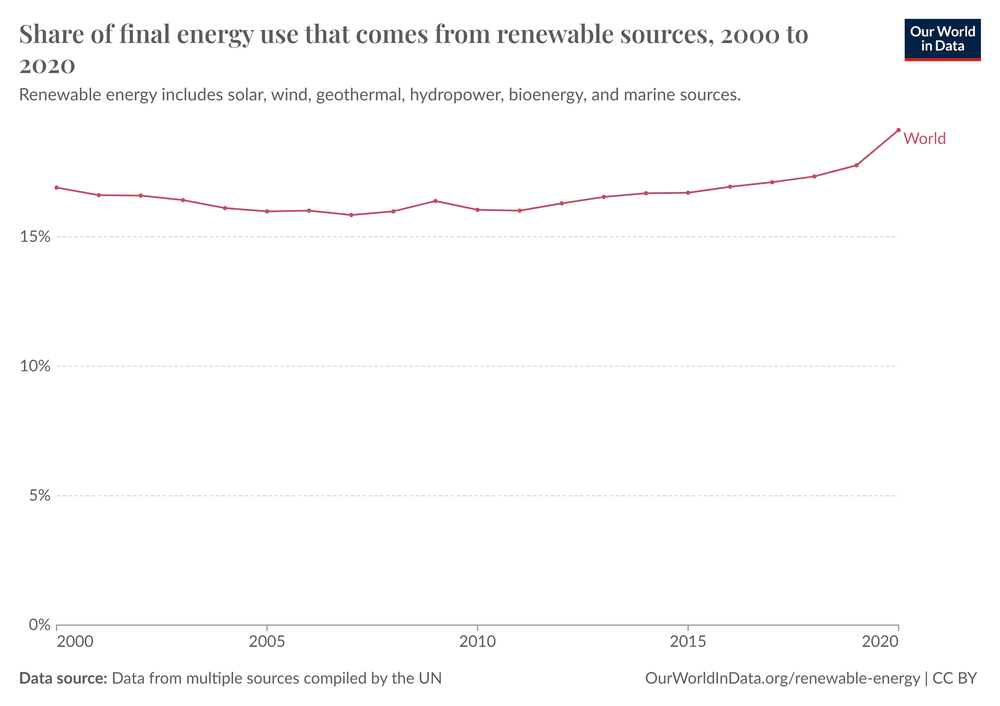

The renewable energy share in final energy consumption worldwide is 19% using 2020 data, far from this target’s aim of universal access to move away from the emission of carbon dioxide.

SDG Target #7.1

SDG #7 is to “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.”

Within SDG #6 are 5 targets, of which we here focus on Target 7.1:

By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services

Target 7.1 has two indicators:

Indicator 7.1.1: Proportion of population with access to electricity

Indicator 7.1.2: Proportion of population with primary reliance on clean fuels and technology

The obvious importance of electricity access lies as it’s a marker of living standards, as well as a necessity for health.

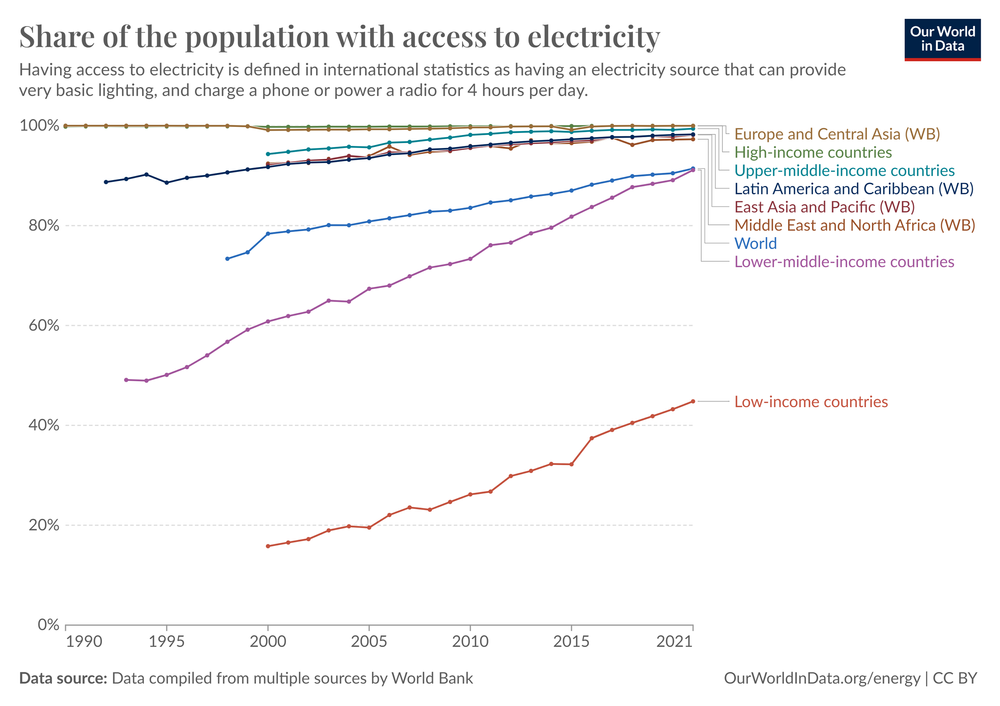

The World Bank has measured access to electricity worldwide to be 91% as of 2021. To break this up, Europe and Central Asia have full electrification, as do the high-income and the upper-middle income countries. The regions of the Middle East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean and East Asia and the Pacific have between 97-98%. The lower-middle income countries have a similar proportion to the global population. 45% in low-income countries have electricity.

As we saw in Target 3.9, air pollution from stoves burning solid cooking fuels in households in some developing countries is a health risk. By contrast, in high-income countries, households tend to use cooking and energy methods not posing a health risk. Dirty fuels also pose affect the environment and contribute to climate change.

The World Health Organization estimates access to clean cooking fuels to be 71% of the world population.

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #6.b

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.b:

Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management

Target 6.b has one indicator:

Indicator 6.b.1: Proportion of local administrative units with established and operational policies and procedures for participation of local communities in water and sanitation management

The data for this target draws from UN Water’s Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS). The World Health Organization puts this assessment into effect.

We’re here looking at water at the local government level. A handy tool is the OECD’s Water Governance Indicator Framework to assess policies. This framework is part of the OECD’s water program, which advises governments on water policies. The OECD also has 12 Principles on Water Governance it recommends for governments.

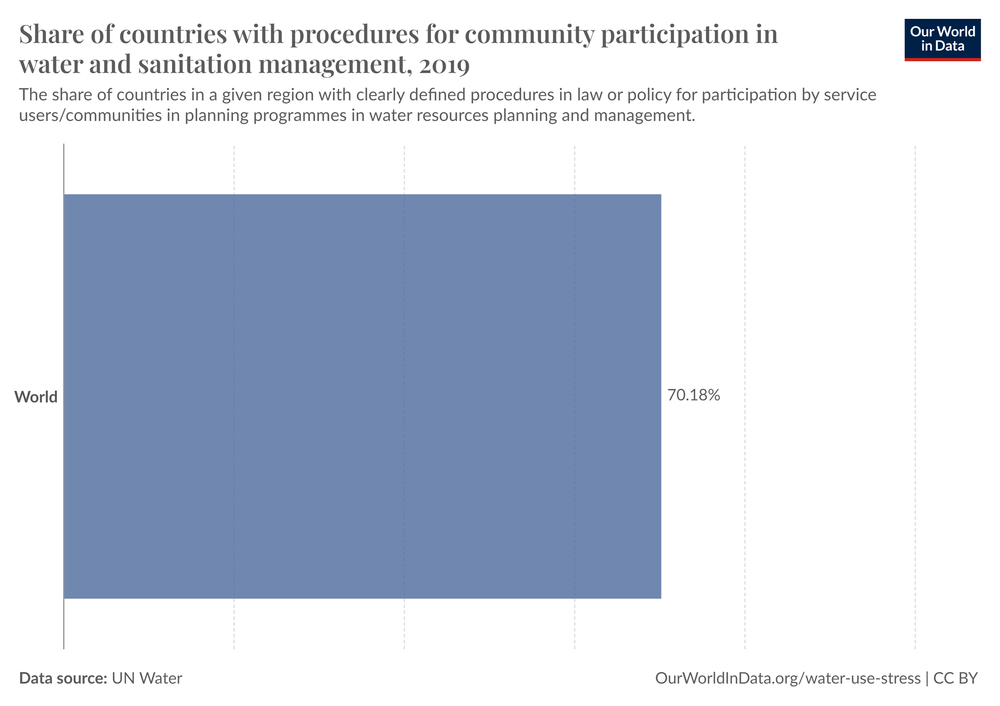

As of 2019, 70% of countries had in place policies and procedures for community participation in water and sanitation.

SDG Target #6.a

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.a:

By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies

Target 6.a has one indicator:

Indicator 6.a.1: Amount of water- and sanitation-related official development assistance that is part of a government-coordinated spending plan

Using the OECD’s Creditor Reporting System, we can disaggregate development flows by type. In this instance, we want to separate out water aid.

Let's look at ODA spent on water as part of a government’s budget. As of 2021, the biggest spender was India, with $420 million. Following was Vietnam and Cambodia, with $413 million and $309 million, then Bangladesh with $284 million and Egypt with $261 million.

SDG Target #6.5

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.5:

By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate

Target 6.5 has two indicators:

Indicator 6.5.1: Degree of integrated water resources management

Indicator 6.5.2: Proportion of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation

What is integrated water resources management (IWRM)? In some ways, it’s reflective of the concept of sustainable development as it relates to water. It means to devise and put into effect a system which manages water resources with several considerations. It needs to consider the economic, social, and in particular the environmental aspects. At the governmental level, it can involve the coordination of several ministries. These might include the portfolios of water, planning, land, agriculture, and rural development.

Managing water resources is of utmost importance for the environment. But it also has large social, and economic implications in water scarce regions such as Western Asia and Africa. Every drop seems to count to ensure dignity and prosperity in these regions.

The Global Water Partnership, a network of over 3000 water organisations, and DHI, support such efforts. Managing water is relevant not only at the national level, but across countries within regions sharing a common border. It likewise has importance across administrative divisions within countries.

This issue of water resources shared across borders brings us to Indicator 6.5.2. This is relevant whether a shared water body is visible on the surface, or groundwater in an aquifer. This topic seems ripe for conflict in water scare regions, and as such, competing interests need managing. International treaties between nations on the sustainable use of transboundary freshwater aid this. The most prominent example is the 1997 Water Convention.

The degree to which an integrated water resources management plan is in effect across all countries worldwide is 54% as of 2020. France and Singapore lead with 100% implementation. A half-dozen countries score 0, among them Argentina, Canada, and Venezuela.

41% of global aquifers have transboundary basins with arrangements to cooperate over water as of 2022. 65% of river and lake basins have such coverage, with 58% for both combined.

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #6.4

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.4:

By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity

Target 6.4 has two indicators:

Indicator 6.4.1: Change in water-use efficiency over time

Indicator 6.4.2: Level of water stress: freshwater withdrawal as a proportion of available freshwater resources

It’s valuable to consider all the different activities which call upon water resources. These include the immense requirements of the primary industries of agriculture and resource extraction. Then there’s the secondary sectors of manufacturing, construction, plus the supply of power, as well as sewerage and waste treatment, as well as domestic water supply.

Water use efficiency is a measure in monetary terms, denominated in US dollars per cubic metre. At the country level, this means we take the GDP, and divide it by the number of cubic metres of freshwater withdrawn, to give us the water efficiency.

Worldwide, water efficiency in 2020 was $21 per cubic metre. Let's compare this figure for the best and worst performers among countries with data. The tiny country of Luxembourg had $1,379 per cubic metre the most water efficient, and Madagascar was the worst with $0.91/m3.

We become at risk of water stress when we withdraw freshwater at a rate faster than it can renew, minus what the environment needs. As of 2020, there’s 42 billion cubic metres of renewable water in the world, with an annual freshwater withdrawal rate of 3.8 billion cubic metres. We can calculate this to tell us how water stressed a country is. First, we take the amount of freshwater withdrawn (measured in cubic metres). We then divide this by the total renewable freshwater, minus the environment requirements. After multiplying by 100, this gives us a percentage of water stress, which if greater than 75%, is high. Besides affecting our drinking water supply and economic sectors, this threatens food security.

Measured at the global level, the level of water stress is 18% as of 2020. This level hasn't changed since 2015, although the target has asked us to reduce those living with water scarcity. Several countries even have a critical water stress percentage greater than 100. This occurs when we withdraw freshwater at a greater rate than the renewable sources can replenish. These countries span the Sahara, across the Mideast into Central Asia. Kuwait’s water efficiency percentage is a stratospheric 3,850%, followed by 1,587% in UAE and 974% in Saudi Arabia. Not only has Kuwait not decreased its water scarcity, its doubled it since 2000.

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #6.3

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.3:

By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally

Target 6.3 has two indicators:

Indicator 6.3.1: Proportion of domestic and industrial wastewater flows safely treated

Indicator 6.3.2: Proportion of bodies of water with good ambient water quality

The proportion of treated domestic wastewater worldwide stands at 57% as of 2022. Very few countries have enough data to report treatment for industrial wastewater.

The global proportion of water bodies with good water quality stands at 71% as of 2020.

SDG Target #6.2

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.2:

By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations

Target 6.2 has one indicator:

Indicator 6.2.1: Proportion of population using (a) safely managed sanitation services and (b) a handwashing facility with soap and water

UNICEF and the World Health Organization have teamed up to report the progress on this issue under the banner of the JMP. This stands for the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH).

The worldwide proportion of people with access to sanitation facilities is 56% as of 2022 and 75% for handwashing facilities.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #6.1

SDG #6 is to “Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all”

Within SDG #6 are 8 targets, of which we here focus on Target 6.1:

By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all

Target 6.1 has one indicator:

Indicator 6.1.1: Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services

SDG #6 introduces us to UN Water, coordinating the efforts of all the other UN agencies on the topic of water and sanitation. WHO’s guidelines inform the definition for drinking water quality. Access to safe water is essential to health and disease prevention and lowering the barriers to access is a human right.

The worldwide access to safe drinking water as of 2022 was 72%. Central African Republic had the lowest access among countries with data, with only 6%. Much of this gap is due to where one lives, whereby worldwide, 81% of the urban population have access, but only 62% for those living in rural locations.

SDG Target #5.c

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.c:

Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels

Target 5.c has one indicator:

Indicator 5.c.1: Proportion of countries with systems to track and make public allocations for gender equality and women’s empowerment

Are governments of countries putting their money where their mouth is by putting gender equality and women’s empowerment in law? Are they allocating public finances to put such laws into effect? Are the finance ministries of governments held accountable by the populace to instil equality? Is there an office or ministry, given a budget to spend on such policies in favour of women? If it isn't budgeted for, can a government claim women’s development to be a priority?

As of 2021, the global proportion of countries with systems to track public expenditure on gender equality stands at 26%.

SDG Target #5.b

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.b:

Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology, to promote the empowerment of women

Target 5.b has one indicator:

Indicator 5.b.1: Proportion of individuals who own a mobile telephone, by sex

The definition for the purposes of measurement is access via a public switched telephone network.

As of 2022, 68% of women own a mobile phone in contrast to 77% of men. Among countries with data, all women in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and UAE have mobiles, and only 11% of women in Burundi have access.

SDG Target #5.a

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.a:

Undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance and natural resources, in accordance with national laws

Target 5.a has two indicators:

Indicator 5.a.1: (a) Proportion of total agricultural population with ownership or secure rights over agricultural land, by sex; and (b) share of women among owners or rights-bearers of agricultural land, by type of tenure

Indicator 5.a.2: Proportion of countries where the legal framework (including customary law) guarantees women’s equal rights to land ownership and/or control

Indicator 5.a.1 stipulates to disaggregate the data for the indicator by type of tenure. These types include public, private, communal, indigenous, customary, and informal.

Among the countries with data as of 2022, most are developing countries. Cambodia leads with 88% of women having secure agricultural land rights and 54% of the share of agricultural landowners. Malawi has the largest share with 56%, with Pakistan the least among those with data at 6%.

Indicator 5.a.2 measures gender equality of land ownership rights enshrined in law. Among those countries with data, Ethiopia and Lithuania have the highest guarantees. The lowest guarantees in the legal frameworks for equal land ownership are in Lebanon and Mauritania.

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #5.6

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.6:

Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed in accordance with the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action and the outcome documents of their review conferences

Target 5.6 has two indicators:

Indicator 5.6.1: Proportion of women aged 15–49 years who make their own informed decisions regarding sexual relations, contraceptive use and reproductive health care

Indicator 5.6.2: Number of countries with laws and regulations that guarantee full and equal access to women and men aged 15 years and older to sexual and reproductive health care, information and education

This target introduces us to the topics of population as it relates to women. This issue, as well as sexual and reproductive health and rights, is overseen at the UN level by the UNFPA (UN Population Fund). From this arises the question for women worldwide on who’s making the decision about their own healthcare. Do women have the choice to use contraceptives, and can they refuse sex with a partner if they don’t want to? The fertility rates are highest in these countries, yet so are the child mortality rates. Some families choose to have more children to compensate. Many women in such regions have choice deprived of them around their reproductive decisions. But development allows women to delay childbirth and reduces the child mortality and fertility rates. It's also easier to meet the existing population’s basic needs when there’s less mouths to share it with.

Target #5.6 mentions to International Conference on Population and Development. This 1994 UNFPA conference addressed the pressures of population, fertility, and development. The ICPD also highlighted the issue of women’s rights to their own decision-making on matters relating to sex and reproduction.

This extends to the laws in effect in respective countries upholding such rights. These include matters of:

Maternity care

Contraception and family planning, including the topic of the morning after pill

Sex education, including the teaching of consent

HIV and HPV

Abortion

Consideration of the age children and adolescents can consent to their own medical treatment

Child sexual exploitation

This target also mentions the Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action, mentioned already in this series in Target 5.1.

56% of women worldwide make their own informed decisions about sexual relations and contraceptive use. The lowest rates are in sub-Saharan Africa, where only 37% of women face such choices.

76% of countries have laws as of 2022 ensuring the right to access sexual and reproductive health care for both sexes.

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #5.5

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.5:

Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life

Target 5.5 has two indicators:

Indicator 5.5.1: Proportion of seats held by women in (a) national parliaments and (b) local governments

Indicator 5.5.2: Proportion of women in managerial positions

Indicator 5.5.1 introduces us to the work of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). The IPU is independent of the UN, but the two work together. Indicator 5.5.1 is split into two levels of governance: national parliaments and local governments. For the countries with data, UN Women reports 3 million elected to local government.

As of 2023, the global share of women in parliamentary seats is 26%, with the most in Rwanda, with 61%. For the same in local government, the global figure is 35%, the largest share being in Antigua and Barbuda.

Let's turn from positions of leadership in government to the world of work and the labour force for the second indicator for Target 5.5. We now measure what share of women have a managerial occupation. Of the countries with data, Jordan has the largest share of women in senior and middle management positions with 57%. The worldwide share of organisations with the top manager being female is 18%, with the greatest share of countries with data in Thailand (64%).

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #5.4

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.4:

Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate

Target 5.4 has one indicator:

Indicator 5.4.1: Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, by sex, age and location

Unemployed individuals, or those performing unpaid work, are seldom recognised for their contribution. They’re underutilised in the use of their time from an economic and social perspective. This has relevance when considering gender across the globe.

Many countries don’t have data for this indicator. Of the countries with data, the biggest disparity between the sexes in time spent on unpaid work is Mexico. In 2022, Mexican men spent 11% of their time each day on unpaid work, and women 27%. Indicator 5.4.1 asks of us to disaggregate the data by location. To separate Mexico’s 2019 data, 30% of the time of rural women was unpaid work compared to 26% for urban women. Rural men spent 10% of their time on unpaid work, and 11% for urban men in Mexico.

SDG Target #5.3

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.3:

Eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation

Target 5.3 has two indicators:

Indicator 5.3.1: Proportion of women aged 20–24 years who were married or in a union before age 15 and before age 18

Indicator 5.3.2: Proportion of girls and women aged 15–49 years who have undergone female genital mutilation, by age

The worldwide proportion of women married before age 15 was 4% as of 2022. We don’t have worldwide data for women married under age 18. But among countries with data, the highest rates were in Niger, where 76% of women married before 18.

Unpleasant as it may to be to discuss, imagine how much worse it could be to experience female genital mutilation. 230 million females experience this practice, often when girls are not yet adults.

UN agencies have collaborated to present the statement entitled Eliminating female genital mutilation. The statement approaches the topic from many perspectives:

health

human rights

development

social and cultural practices

children’s rights

women’s rights

reproductive rights.

The countries with rates of female genital mutilation greater than 80% of the female population as of 2020 include:

Mali

Guinea

Sierra Leone

Egypt

Sudan

Eritrea

Somalia (99% rate)

View fullsize

SDG Target #5.2

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.2:

Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation

Target 5.2 has two indicators:

Indicator 5.2.1: Proportion of ever-partnered women and girls aged 15 years and older subjected to physical, sexual or psychological violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months, by form of violence and by age

Indicator 5.2.2: Proportion of women and girls aged 15 years and older subjected to sexual violence by persons other than an intimate partner in the previous 12 months, by age and place of occurrence

This target focuses on violence against women and intimate partner violence. These are not only crimes in many countries, but violations of human rights agreed upon at the international level in the form of treaties. Looked at from a public health perspective, the threat it poses to the health of a population is of pandemic proportions. Let’s look at some of the forms countries enshrine and affirm this right.

The most relevant to this topic is the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1993. This violence can be physical, sexual, or psychological, whether or not committed by an intimate partner.

The same principles are also reflected in the following human rights agreements:

Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration is international law for those who signed and ratified via two treaties adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1966:

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. All but 20 countries are states parties. Those who’ve not acted include South Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Bhutan, Malaysia, Myanmar, with China signing but not ratifying.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. In this instance the US is the main holdout from becoming a state party, having signed but not ratified. Saudi Arabia, the same Gulf states, Malaysia, and Myanmar again haven’t signed. Botswana, Mozambique and about 20 other smaller countries also haven't signed or ratified.

In the previous target, we already looked at the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. The General Assembly adopted this treaty in 1984. The largest country which isn't a state party is India, which has signed but not ratified. Other non-signatories are Bangladesh, Eswatini, Iran, Myanmar, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea and other smaller countries.

The advancement of women has been a focus of the UN since the UN Decade for Women from 1975-85. For 68 annual sessions, as of 2024, the UN Women’s Commission on the Status of Women has met to advance women’s empowerment and gender equality.

How prevalent is the crime of violence against women worldwide, across regions and countries? How do we know? Much violence against women occurs out of sight, behind closed doors. For this information, we can look to three main international sources. Several UN agencies work together to collate this data for measurement. 10% of women over 15-years-old worldwide experienced physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner in the past 12 months. The highest proportions were in Democratic Republic of Congo and Afghanistan, both reporting above 30%.

SDG Target #5.1

SDG #5 is to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”

Within SDG #5 are 9 targets, of which we here focus on Target 5.1:

End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere

Target 5.1 has one indicator:

Indicator 5.1.1: Whether or not legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce and monitor equality and non‑discrimination on the basis of sex

This target will introduce us to UN Women, the UN body charged with the task of achieving gender equality, one of the pillars of development. Many developing countries need help to meet this target's aim. The high-income countries of the OECD can help developing countries to promote such standards. This is because of the intrinsic tie between gender inequality and sustainable development.

What do countries need to put such legal frameworks into effect? Countries need to promote the adoption of laws affecting the life of women, then enforce and track them. Such laws need to cover the topics of violence against women. They also need to address employment, to ensure women enjoy economic benefits, and also marriage and family.

What is the primary guiding principle in considering legal frameworks to end discrimination? Let's look to Article 1 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). It defines discrimination against women as:

“...distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”

The States Parties to the CEDAW are all countries except the US, Iran, Sudan, Somalia, Palau (which is in free association with the US) and Tonga.

Another landmark guidance for intergovernmental progress in advancing gender equality occurred in Beijing. It's known as Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted in 1995 and affirmed five years later in Beijing in 2000.

Worldwide, as of 2022, 70% of countries have a legal framework addressing gender equality. 78% of countries have legal frameworks addressing violence against women as of 2022. 76% have legal frameworks addressing gender equality as it relates to employment and economic benefits. 79% of countries have legal frameworks addressing gender in relation to marriage and family.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #4.c

SDG #5 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.c:

By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing States

Target 4.c has one indicator:

Indicator 4.c.1: Proportion of teachers with the minimum required qualifications, by education level

As of 2019, the proportion of pre-primary teachers with the minimum required qualifications in the least developed countries (LDCs) was 63% and 72% in the small island developing countries (SIDS). For primary school teachers, the 2020 proportion was 79% for SIDS and 72% for LDCs and 86% worldwide. For each, the increase since 2015 was a couple percentage points. For lower secondary school in 2020, worldwide 83% of teachers had the minimum qualifications, 63% for LDCs and 75% for SIDS. For upper secondary in 2020, 89% of teachers in the SIDS had minimum qualifications, 85% worldwide, and 58% in LDCs.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #4.b

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.b:

By 2020, substantially expand globally the number of scholarships available to developing countries, in particular least developed countries, small island developing States and African countries, for enrolment in higher education, including vocational training and information and communications technology, technical, engineering and scientific programmes, in developed countries and other developing countries

Target 4.b has one indicator:

Indicator 4.b.1: Volume of official development assistance flows for scholarships by sector and type of study

This indicator reintroduces us to the concept of official development assistance (ODA). Otherwise known as foreign aid, the high-income OECD countries bear the responsibility to donate ODA. These donor countries form the OECD's Development Assistance Committee (DAC) to offer aid flows to the list of ODA recipients. This target focuses on ODA for scholarships to finance the development of education systems.

To track the progress for this target and indicator, let’s look at the development flows to the respective regions mentioned in the body of target 4.b. For African countries, as of 2021, ODA intended for scholarships was $US297 million, an increase from $US225 million from 2015. For developing countries, aid for scholarships in 2021 was $1.35 billion, down from $1.49 billion in 2015. For the least developed countries, 2021 scholarship aid was $221 million, down from $225 million in 2015. For the Small Islands Developing States, scholarship aid was $43 million in 2021, down from $104 million in 2015.

SDG Target #4.a

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.a:

Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all

Target 4.a has one indicator:

Indicator 4.a.1: Proportion of schools offering basic services, by type of service

Key to achieving this in the modern-day is access to information and communication technologies. ICTs allow even the remotest schools and children to access education systems. It even allows the possibility to access some of the best education institutions in the world. Schools need electricity to power the information and communication technologies. They also need an internet connection and computers for teaching and learning. Still, solutions to achieve this are available at low-cost.

The infrastructure of the learning environment also needs to adapt to be suitable for those with a disability. The learning materials need to factor in disabled students also.

School facilities also need basic facilities for drinking water, sanitation, and handwashing.

Let's look at the worldwide progress toward this target and indicator. The proportion of schools offering the basic service of access to electricity as of 2020 was 90% in upper secondary, and 75% in primary. 80% of secondary schools offered access to handwashing facilities, and 76% of primary schools. 84% of secondary schools offered access to drinking water, and 75% of primary schools. 76% of upper secondary schools offered access to computers, and 46% of primary schools. The proportion of primary schools offering internet access for the purposes of teaching worldwide in 2022 was 39%. 89% of secondary schools offered single-sex toilets worldwide in 2020, and 76% of primary schools. 56% of secondary schools offered learning materials and infrastructure adapted to disabled students. This proportion was 47% for primary schools.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #4.7

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.7:

By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

Target 4.7 has one indicator:

Indicator 4.7.1: Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education; and (d) student assessment

For us to have peace and sustainable development, we first need to educate ourselves on what sustainable development is. How we achieve it is the foundation for peace. The issues the SDGs place before are urgent. But we can take actions to foster sustainable development to keep at bay the most sudden and striking outcomes on our planet. Our world is interdependent, and whether we choose to be or not, we’re global citizens.

But what does it mean to be a good global citizen? Like anything in life, to light the way, we need an education in global citizenship. In this way, we can go on to contribute, whatever our age, and this opportunity ought to inspire us all. Education to foster understanding across countries, as well as being a human right, opens a world of freedom for the learner.

The responsibility to put in place this right of citizens in each country lies with the relevant ministries of education. But we have an opportunity at the international level for member states to cooperate via UNESCO’s efforts.

UNESCO has issued a recommendation document outlining how governments should foster such education. Recommendations are part of the legal jargon of UNESCO to set standards for member states to put into practice or law.

The results for this indicator are encouraging among the countries with data. We're measuring the extent of mainstreaming global citizenship and sustainable development education. The unit of measure is an index, where 0 is the worst and 1 the best. Most reporting countries record indexes greater than 0.8 for mainstreaming in national education. The results are similar for mainstreaming in curricula, teacher education and student assessment.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #4.6

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.6:

By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy

Target 4.6 has one indicator:

Indicator 4.6.1: Proportion of population in a given age group achieving at least a fixed level of proficiency in functional (a) literacy and (b) numeracy skills, by sex

This indicator introduces us to the concept of fixed level of proficiency. This is a standard of knowledge in a field of learning - in this instance, literacy and numeracy.

To survey the skills of adults, the OECD runs the PIAAC. This stands for Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. This program can assess adults in literacy and numeracy.

What are the worldwide literacy rates of people between 15-24 years old? As of 2020, disaggregated by sex as defined by the indicator, it's 93% for men and 90% for women, with only a fractional increase since 2015.

The worldwide literacy rate for males over 15 was 90% in 2020, and 83% for females. But as of 2017, UNESCO has insufficient data across the countries to form a global numeracy rate disaggregated by sex.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

SDG Target #4.5

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.5:

By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations

Target 4.5 has one indicator:

Indicator 4.5.1: Parity indices (female/male, rural/urban, bottom/top wealth quintile and others such as disability status, indigenous peoples and conflict-affected, as data become available) for all education indicators on this list that can be disaggregated

Whilst for this indicator, there isn’t one global parity index for gender equality, disability, and indigenous people. We do have some data for individual countries.

Those with a 2021 gender parity for primary completion lower than 0.8, meaning less 8 girls for every 10 boys, were Yemen, Somalia, and Afghanistan. The latter two had parities closer to 7 girls for every boy.

What about secondary completion? A half-dozen other countries in sub-Saharan Africa with 2021 data had parity rates across the sexes below 7 girls for every 10 boys. The lowest secondary completion gender parities were in Chad and Somalia, where 0.35 girls completed secondary per boy.

SDG Target #4.4

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.4:

By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship

Target 4.4 has one indicator:

Indicator 4.4.1: Proportion of youth and adults with information and communications technology (ICT) skills, by type of skill

The mention of ICT’s introduces us to the UN agency specialising in this field, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

To measure these skills at the international level, in 2020, the ITU has issued a manual to measure access of individuals and households. This gives us 50 indicators for a variety of ICT skills, grouped into several categories.

An example is being able to receive and send SMS. Another is using VoIP technologies to make voice calls and send messages over broadband internet.

It’s imperative across countries for individuals and households to have access to and use ICT’s. The world must progress toward greater connection. This is a reflection of the value of digital knowledge and the information societies we’ve become. In this way, telecommunication is key to development. The importance of ICT extends beyond the individual and household to education. It also offers opportunities for governments and enterprises, and the infrastructure for this needs to be there to begin with.

SDG Target #4.3

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.3:

By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

Target 4.3 has one indicator:

Indicator 4.3.1: Participation rate of youth and adults in formal and non-formal education and training in the previous 12 months, by sex

The more training and education undertaken by a population, the greater the participation in the labour force, and for individuals to find employment and avoid unemployment and underemployment in working the number of hours one wishes to.

Worldwide, the enrolment rate for tertiary education as of 2022 was 41%, up from 36% in 2015, at the adoption of the SDGs.

SDG Target #4.2

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.2:

By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education

Target 4.2 has two indicators:

Indicator 4.2.1: Proportion of children aged 24–59 months who are developmentally on track in health, learning and psychosocial well-being, by sex

Indicator 4.2.2: Participation rate in organised learning (one year before the official primary entry age), by sex

The UN agency responsible for monitoring the first indicator for this target is UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), focused upon children. The indicator is served by UNICEF’s Early Childhood Development Index 2030, a tool to measure this indicator’s progress. The science underlying early childhood development has revealed it as a crucial intervention in the effective nurturing and care in a child’s overall development, and the SDGs present an opportunity to expand and implement such findings to the greatest possible scale.

Worldwide, as of 2022, only 69% of children aged 3 to 5 are on track in health, learning and psychosocial well-being.

The second indicator for this target looks at pre-school, defined according to UNESCO’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The ISCED exists to provide uniformity across the different education structures and curricula across countries.

As of 2020, 74% of children at the age of one year before primary entry were enrolled in organised learning, about the same as 2015, at the adoption of the Global Goals. Disaggregated by sex, per the definition of the indicator, the enrolment of both sexes was at parity as of 2022.

SDG Target #4.1

SDG #4 is to “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Within SDG #4 are 10 targets, of which we here focus on Target 4.1:

By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to a relevant and effective learning outcome.

Target 4.1 has two indicators:

Indicator 4.1.1: Proportion of children and young people (a) in grade 2/3; (b) at the end of primary; and (c) at the end of lower secondary achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in (i) reading and (ii) Mathematics, by sex

Indicator 4.1.2: Completion rate (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education)

Indicator 4.1.1 looks at minimum proficiency levels. This is the benchmark of basic knowledge, as measured by assessments, in this instance, for reading and mathematics. This indicator looks at reading and maths skills at three points: grade 2 and 3, end of primary schooling, and end of lower secondary. Performance level descriptors describe the knowledge and skills demonstrated by students at each. Performance level descriptors help us to assess students across countries.

Let's look at the respective descriptors for each grade.

Reading, grade 2: Being able to read and comprehend familiar written words and extract explicit information from sentences.

Reading, grade 3: Read written words aloud, understanding the meaning of sentences and short texts and identifying the topic.

Maths, grades 2/3: To make sense of, calculate numbers, and recognise shapes.

Reading, end of primary: Interpreting and giving explanations about the main and secondary ideas in different texts and establishing connections between main ideas and their own experiences.

Maths, end of primary: Basic measurement and reading and creating graphs.

Reading, end of lower secondary schooling: Establishing connections of the author’s intentions and reflecting and drawing conclusions based on the text.

Maths, end of lower secondary school: Solving maths problems, using tables and graphs, as well as algebra.

The data for assessing trends in students draws from a half-dozen surveys, some run by UNICEF and UNESCO. UNESCO the UN’s agency focused on education. The purpose of these assessments is to survey the effectiveness of learning outcomes. In some countries, it’s possible for a student to pass through grades without meeting the minimum proficiency levels.

International large-scale assessments test educational outcomes. An example is PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) for reading literacy in grade 4 students.

There are also several large-scale learning assessments at the national and regional level. UNESCO’s office in Santiago houses the bureau focused on education in the Latin American and Caribbean region. This includes the LLECE, the Spanish acronym for the Latin American Laboratory for Evaluation of the Quality of Education. The LLECE runs the ERCE, the Spanish acronym for the Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study, a major large-scale learning assessment for the region.

Other examples of large-scale learning assessments at the regional level include:

SEACMEQ (Southern and Eastern African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality)

Pacific Community’s Pacific Islands Literacy and Numeracy Assessment

SEAMEO (Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization)

The benefit of these surveys is they serve as tools to provide the evidence which then goes toward making decisions to improve education. This then serves those children not attaining the expected learning outcomes for their grade level.

As of 2019, the proportion of students worldwide at the end of primary education meeting minimum proficiency levels in reading was 58%. This was down 1% since the start of the SDG period in 2015. For maths at the same level, the worldwide share of minimum proficiency was 44%, and 50% for lower secondary in mathematics.

To coincide with the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, the UN released a report, titled Education 2030. The Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action accompanied the report. This declaration's name came from the South Korean city hosting UNESCO’s World Education Forum 2015 conference. Education 2030 is an effort of several UN agencies besides UNESCO, including the UNDP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UN Women, the World Bank Group and ILO. The purposes of the report, as well as the Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action, reinforces the purpose of SDG #2.

The aim is to end Learning Poverty, which the World Bank defines as 10-year-olds being unable to read and understand a simple story.

The second indicator for this target looks at school completion of primary, lower secondary and upper secondary.

The completion rate for primary education worldwide was 87% as if 2021, up only 2% since 2015. Lower secondary completion rates were 77% in 2020, again up only 2% since 2015. Global upper secondary completion was 58% as of 2021, up 5% since 2015.

SDG Target #3.d

SDG #3 is to “To ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

Within SDG #3 are 13 targets, of which we here focus on Target 3.d:

Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks.

Target 3.d has two indicators:

Indicator 3.d.1: International Health Regulations (IHR) capacity and health emergency preparedness

Indicator 3.d.2: Percentage of bloodstream infections due to selected antimicrobial resistant organisms.

This target and indicators look at the security aspects of health, inclusive of emergency management, aiming to increase the ability of all World Health Organisation member states to prepare for public health emergencies, such as the world has experienced with COVID-19.

Much of how World Health Organisation states-parties are to behave in relation to one another to prevent global pandemics is guided by the WHO’s International Health Regulations, as mentioned in this target’s first indicator. The respective WHO states-parties are obliged to self-report each year on their adherence and capacities for the International Health Regulations.

The self-assessment tool has 15 indications for WHO members, ranging from legislation; financing; zoonotic diseases of human-animal crossover, which account for 75% of emerging pathogens; coordination between countries to notify the WHO of events which pose a global health risk; food safety, and preventing and controlling infections, among others. Further, each country is to post their self-assessment in fulfilling the International Health Regulations online via the public e-SPAR platform.

The second indicator of this target looks at bloodstream infections due to selected antimicrobial-resistant organisms. These organisms include a variety of the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus which is resistant to the antibiotic methicillin, a type of penicillin. Also, the bacterium E. coli. produces an enzyme which is resistant to a type of antibiotics called cephalosporins.

One of the methods clinical laboratories can use to test whether a microorganism may be susceptible to antibiotics is known as a broth microdilution. Antimicrobial resistance occurs when viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites change in the ways by which drugs once used to treat against them either have less efficacy or no longer work. The greater difficulty caused by treating infections of such microorganisms in turn can be the cause of greater infectivity and spread of disease, as well as the possibility of such diseases being more fatal.

One of the initiatives the World Health Organization exercises against this threat is the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) to help countries surveil for such developments of drug resistance in known microorganisms.

For the second indicator of this target, the global share of Staphylococcus aureus infections resistant to methicillin stood at 31% as of 2021, up from 20% in 2016. E. coli infections resistant to cephalosporins stands at a global total of 39% in 2021, up from 35% in 2016, and experiencing an almost doubling in 2018, before coming back down.

SDG Target #3.c

SDG #3 is to “To ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

Within SDG #3 are 13 targets, of which we here focus on Target 3.c: