- Affärsnyheter

- Alternativ hälsa

- Amerikansk fotboll

- Andlighet

- Animering och manga

- Astronomi

- Barn och familj

- Baseball

- Basket

- Berättelser för barn

- Böcker

- Brottning

- Buddhism

- Dagliga nyheter

- Dans och teater

- Design

- Djur

- Dokumentär

- Drama

- Efterprogram

- Entreprenörskap

- Fantasysporter

- Filmhistoria

- Filmintervjuer

- Filmrecensioner

- Filosofi

- Flyg

- Föräldraskap

- Fordon

- Fotboll

- Fritid

- Fysik

- Geovetenskap

- Golf

- Hälsa och motion

- Hantverk

- Hinduism

- Historia

- Hobbies

- Hockey

- Hus och trädgård

- Ideell

- Improvisering

- Investering

- Islam

- Judendom

- Karriär

- Kemi

- Komedi

- Komedifiktion

- Komediintervjuer

- Konst

- Kristendom

- Kurser

- Ledarskap

- Life Science

- Löpning

- Marknadsföring

- Mat

- Matematik

- Medicin

- Mental hälsa

- Mode och skönhet

- Motion

- Musik

- Musikhistoria

- Musikintervjuer

- Musikkommentarer

- Näringslära

- Näringsliv

- Natur

- Naturvetenskap

- Nyheter

- Nyhetskommentarer

- Personliga dagböcker

- Platser och resor

- Poddar

- Politik

- Relationer

- Religion

- Religion och spiritualitet

- Rugby

- Så gör man

- Sällskapsspel

- Samhälle och kultur

- Samhällsvetenskap

- Science fiction

- Sexualitet

- Simning

- Självhjälp

- Skönlitteratur

- Spel

- Sport

- Sportnyheter

- Språkkurs

- Stat och kommun

- Ståupp

- Tekniknyheter

- Teknologi

- Tennis

- TV och film

- TV-recensioner

- Underhållningsnyheter

- Utbildning

- Utbildning för barn

- Verkliga brott

- Vetenskap

- Vildmarken

- Visuell konst

History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences

History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences explores the history of the study of language in its varied social and cultural contexts.

47 avsnitt • Längd: 25 min • Oregelbundet

Om podden

History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences explores the history of the study of language in its varied social and cultural contexts.

The podcast History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences is created by James McElvenny. The podcast and the artwork on this page are embedded on this page using the public podcast feed (RSS).

Avsnitt

Podcast episode 45: Beijia Chen on Neogrammarian networks

In this interview, we talk to Beijia Chen about the citation networks binding the Neogrammarians as a school.

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | YouTube

References for Episode 45

Amsterdamska, Olga. 1985. “Institutions and Schools of Thought: The Neogrammarians.” American Journal of Sociology 91: 332–358.

Amsterdamska, Olga. 1987. Schools of thought: the development of linguistics from Bopp to Saussure. Dordrecht u.a.: Reidel.

Arens, Hans. 1969. Sprachwissenschaft: der Gang ihrer Entwicklung von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. 2., durchges. und stark erw. Auflage. Freiburg & München: Alber.

Bartschat, Brigitte. 1996. Methoden der Sprachwissenschaft: von Hermann Paul bis Noam Chomsky. Berlin: Schmidt.

Beveridge, Andrew & Jie Shan. 2015. “Network of Thrones.” Math Horizons 23 (4): 18–22.

Chen, Beijia. 2020. “Der Einfluss der akademischen Interaktionen auf die Auflagen- und Wirkungsgeschichte von Hermann Pauls Prinzipien.” Historiographia LInguistica 47 (2–3): 188–230.

Crane, Diana. 1972. Invisible Colleges: Diffusion of Knowledge in Scientific Communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Einhauser, Eveline. 1989. Die Junggrammatiker: ein Problem für die Sprachwissenschaftsgeschichtsschreibung. Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

Fangerau, Heiner. 2009. “Der Austausch von Wissen und die rekonstruktive Visualisierung formeller und informeller Denkkollektive.” In Netzwerke: Allgemeine Theorie oder Universalmetapher in den Wissenschaften? Ein transdisziplinärer Überblick, edited by Heiner Fangerau & Thorsten Halling, 215–246. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Fangerau, Heiner & Klaus Hentschel. 2018. “Netzwerkanalysen in der Medizin- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte – Zur Einführung.” Sudhoffs Archiv 102 (2): 133–145.

Fleck, Ludwik. 1980 [1935]. Entstehung und Entwicklung einer wissenschaftlichen Tatsache. Einführung in die Lehre vom Denkstil und Denkkollektiv. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Goldsmith, John A. & Bernard Laks. 2019. Battle in the Mind Fields. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

Haas, Stefan. 2014. “Begrenzte Halbwertzeiten.” Indes 3 (3): 36–43.

Harnack, Adolf von. 1905. “Vom Großbetrieb der Wissenschaft.” Preußische Jahrbücher 119: 193–201.

Henne, Helmut. 1995. “Germanische und deutsche Philologie im Zeichen der Junggrammatiker.” In Beiträge zur Methodengeschichte der neueren Philologien: zum 125jährigen Bestehen des Max-Niemeyer-Verlags, edited by Robert Harsch-Niemeyer, 1–30. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Hurch, Bernhard. 2009. “Von der Peripherie ins Zentrum: Hugo Schuchardt und die Neuerungen der Sprachwissenschaft.” In Kunst und Wissenschaft aus Graz. Bd. 2. 1. Kunst und Geisteswissenschaft aus Graz, edited by Karl Acham, 493–510. Wien: Böhlau.

Jankowsky, Kurt R. 1972. The Neogrammarians: a re-evaluation of their place in the development of linguistic science. The Hague & Paris: Mouton.

Klausnitzer, Ralf. 2005. “Wissenschaftliche Schule.” In Stil, Schule, Disziplin, edited by Lutz Danneberg, Wolfgang Höppner & Ralf Klausnitzer, 31–64. Frankfurt am Main u. a.: Perter Lang.

Knobloch, Clemens. 2019. “Ludwik Fleck und die deutsche Sprachwissenschaft.” Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 47 (3): 569–596.

Koerner, E. F. Konrad. 1976a. “Towards a Historiography of Linguistics. 19th and 20th Century Paradigms.” In History of linguistic thought and contemporary linguistics, edited by Herman Parret, 685–718. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Koerner, E. F. Konrad. 1981. “The Neogrammarian Doctrine: Breakthrough or Extension of the Schleicherian Paradigm. A Problem in Linguistic Historiography.” Folia Linguistica Historica II (2): 157–178.

Kuhn, Thomas S. 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Lakatos, Imre. 1978. The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Philosophical Papers, edited by John Worrall & Gregory Currie. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Leroux, Jean. 2007. “An epistemological assessment of the neogrammarian movement.” In History of Linguistics 2005, edited by Douglas A. Kibbee, 262–273. (Studies in the History of the Language Sciences). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Morpurgo Davies, Anna. 1978. “Analogy, segmentation and the early Neogrammarians.” Transactions of the Philological Society 76 (1): 36–60.

Morpurgo Davies, Anna. 1986. “Karl Brugmann and late nineteenth-century linguistics.” In Studies in history of Western linguistics, edited by Theodora Bynon & Frank Robert Palmer, 150–171. Cambridge et.al.: Cambridge University Press.

Morpurgo Davies, Anna & Giulio Lepschy. 2014 [1998]. History of Linguistics. Volume IV: Nineteenth-Century Linguistics. London & New York: Routledge.

Oesterreicher, Wulf. 1977. “Paradigma und Paradigmenwechsel – Thomas S. Kuhn und die Linguistik.” Osnabrücker Beiträge zur Sprachtheorie 3: 241–284.

Pearson, Bruce L. 1977. “Paradigms and revolutions in linguistics.” Lacus Forum IV: 384–390.

Percival, W. Keith. 1976. “The Applicability of Kuhn’s Paradigms to the History of Linguistics.” Language 52: 285–294.

Price, Derek J. de Solla. 1963. Little Science, Big Science. New York & London: Columbia University Press.

Price, Derek J. de Solla. 1965. “Networks of Scientific Papers.” Science 149 (No. 3683): 510–515.

Putschke, Wolfgang. 1969. “Zur forschungsgeschichtlichen Stellung der junggrammatischen Schule.” Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik 36: 19–48.

Robins, Robert H. 1978. “The neogrammarians and their nineteenth-century predecessors.” In Commemorative Volume: The Neogrammarians 1978, edited by Transactions of the Philological Society, 1–16. Oxford: Basil Blackwell for the Society.

Schippan, Thea. 1978. “Theoretische und methodische Positionen von Darstellungen zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft.” Zeitschrift für Phonetik, Sprachwissenschaft und Kommunikationsforschung 31: 476–481.

Storost, Jürgen. 1990. “Sechs maßgebende linguistische Fachzeitschriften in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts.” Zeitschrift für Germanistik 11 (3): 303–318.

Weingart, Peter. 2003. Wissenschaftssoziologie. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Zawrel, Sandra. 2015. Funktion und Organisation germanistischer Fachzeitschriften in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Eine Analyse am Beispiel der Germania. Vierteiljahrsschrift für deutsche Altertumskunde (1856-1868) und der Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprache und Literatur (1874-1891). (Alles Buch. Studien der Erlanger Buchwissenschaft LV.) Buchwissenschaft / Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. ISBN 978-3-940338-39-6.

Podcast episode 44: Ian Stewart on the Celts and historical-comparative linguistics

In this interview, we talk to Ian Stewart about modern ideas surrounding the Celts and how these relate to historical-comparative linguistics.

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | YouTube

References for Episode 44

Crump, Margaret, James Cowles Prichard of the Red Lodge: A Life of Science during the Age of Improvement (Nebraska, 2025).

Davies, Caryl, Adfeilion Babel: Agweddau ar Syniadaeth Ieithyddol y Ddeunawfed Ganrif (Caerdydd, 2000).

Droixhe, Daniel, La Linguistique et l’appel de l’histoire (1600-1800): rationalisme et révolutions positivistes (Geneva, 1978).

Lhuyd, Edward, Archaeologia Britannica: Vol. 1 Glossography (Oxford, 1707).

Pezron, Paul-Yves, Antiquité de la nation et de la langue des Celtes, autrement appellez Gaulois (Paris, 1703).

Pictet, Adolph, ‘Lettres à M. A.W. de Schlegel sur l’affinité des langues celtiques avec le sanscrit’, Journal asiatique 3.1 (1836), 263-90, 417-448; 3.2 (1836), 440-66.

Poppe, Erich, ‘Lag es in der Luft?: Johann Kaspar Zeuß und die Konstituierung der Keltologie’, Beiträge zur Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft 2 (1992), 41-56.

Prichard, James Cowles, The Eastern Origin of the Celtic Nations: Proved by a Comparison of their Dialects with the Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, and Teutonic Languages (London, 1831)

Roberts, Brynley F., Edward Lhwyd: c.1660-1709, Naturalist, Antiquary, Philologist (Cardiff, 2022).

Shaw, Francis, ‘The Background to Grammatica Celtica’, Celtica 3 (1956), 1-16.

Sims-Williams, Patrick, Ancient Celtic Place-Names in Europe and Asia Minor (Oxford, 2006).

Sims-Williams, Patrick, ‘An Alternative to “Celtic from the East” and “Celtic from the West”’, Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30 (2020), 511-29.

Solleveld, Floris, ‘Expanding the Comparative View: Humboldt’s Über die Kawi-Sprache and its language materials’, Historiographia Linguistica 47 (2020), 49-78.

Stewart, Ian, The Celts: A Modern History (Princeton, 2025).

Stewart, Ian, ‘After Sir William Jones: British Linguistic Scholarship and European Intellectual History’, Journal of Modern History 95 (2023), 808-846.

Stewart, Ian, ‘James Cowles Prichard and the Linguistic Foundations of Ethnology’, Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte 46 (2023), 76-91.

Van Hal, Toon, ‘Moedertalen en taalmoeders’. Het vroegmoderne taalvergelijkende onderzoek in de Lage Landen (Brussels, 2010).

Van Hal, Toon, ‘When Quotation Marks Matter: Rhellicanus and Boxhornius on the differences between the lingua Gallica and lingua Germanica’, Historiographia Linguistica 38 (2011), 241-52.

Van Hal, Toon, ‘From Alauda to Zythus. The emergence and uses of Old-Gaulish word lists in early modern publications’, Keltische Forschungen 6 (2014), 219-77.

Transcript by Luca Dinu

JMc: Hi, I’m James McElvenny, and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences podcast, online at hiphilangsci.net. [00:16] There you can find links and references to all the literature we discuss. [00:21] Today we’re talking to Ian Stewart, who’s a historian of Britain and Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries and a researcher at the University of Edinburgh. [00:32] Ian’s latest book, The Celts: A Modern History, is coming out in March 2025 with Princeton University Press. [00:42] In this book, Ian offers a path-breaking, and at the same time magisterial, account of how the modern notion of the Celtic nations took shape. [00:51] Linguistic evidence and theorizing, as Ian shows in his book, played no small part in these developments. [00:58] Ian’s also looked at the early history of historical-comparative linguistics in Britain and suggested some key revisions to the standard narrative of how this field took root there. [01:10] The stories of the modern notion of the Celts and of early historical-comparative linguistics in Britain have many points of contact, and this is what Ian will be talking to us about today. [01:21] So, Ian, who are the Celts? [01:23] What was the significance of identifying the so-called Celtic nations in the modern period? [01:30]

IS: Hi, James. [01:32] As you know, I’m a big fan of the podcast, and so it’s really exciting to be here. [01:36] Who are the Celts? [01:38] Well, that depends on who you ask and when. [01:42] It’s a question that’s been asked in many different ways over the last two and a half thousand years, at least. [01:48] To begin with, the Celts are a people who started to be mentioned in classical sources in about 500 BCE. [01:56] Herodotus, for example, refers to them as a people living somewhere in Western Europe. [02:02] In the 4th century BCE, people like Plato and Aristotle refer to them as a warlike people. [02:07] This is especially after a Celtic group sacked Rome in about 387 BCE, and then 100 years later, another group invaded the Balkans. [02:18] And so, you see, the Celts remained the steady presence as a bellicose people somewhere in Europe, but they became sort of less feared as the Romans grew in power. [02:30] Caesar’s famous Gallic Wars, obviously written in the middle of the 1st century BCE, is about the conquest of Gaul, one of whose parts is called Celtica. [02:40] And so, as we move into the first few centuries of the Common Era, references to the Celts start to become fewer, and by 500 CE, you know, they stop altogether. [02:49] So, to sum up, basically, from the classical sources, the Celts are a barbarian people who were fearsome enemies, with their own complicated social, cultural, and religious structures, who feature strongly in the literary record between about 500 BCE and 500 CE. [03:08] The details about this group, or groups, are really hazy. [03:12] They’ve been argued about in all sorts of different ways. [03:15] We don’t know, you know, how much sort of common identification among groups there was, but what we can basically say is that there were people speaking Celtic languages in most of Western and Central Europe, including Britain and Ireland, modern France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Central Europe, Southern Germany, and as far east as Anatolia. [03:38] And so even though the Celts didn’t have their own literary cultures, and even though the historical record left by classical writers is pretty imperfect, the Celts left behind all sorts of evidence — including linguistic evidence, as you alluded to — that later scholars would make use of to construct this picture that we now have. [03:56] Now, why they become important in the modern period is, basically, they become rediscovered during the Renaissance [04:04] — when the predominant approach to history was genealogical, and the origins of nations, regions, cities, dynasties, all sorts of institutions, take on huge importance in establishing legitimacy — [04:19] and so scholars devoted considerable energy in tracing the migrations and conquests of ancient peoples [04:26] in order to give their own nation, or whoever they were writing for, a prestigious pedigree. [04:32] And basically, because of what I just mentioned about their extensive presence in the classical sources, and through their close association with the Gauls especially, the Celts retained this important place in the historical imagination. [04:45] So basically, from the early modern period, it’s off to the races, and they become claimed as prestigious ancestors in all of the countries I mentioned. [04:56] And so, my book is basically about this Celticism, which is basically why people in different places around Europe, from the early modern era to the present, have answered the question, who are the Celts and the way that they did, usually in favor of their own nation. [05:12] They’re usually trying to claim the Celts as their particular special ancestor, and the wranglings over the Celts basically change… [05:23] I sort of say that they’re determined by… basically, that these pictures of national images of ancestry change as a result of scholarly imperatives, but also political imperatives. [05:35] So it’s not just that nations are invented from scratch. [05:39] You know, in the modern period, as some of the literature, some of the classical literature — you know, classical in terms of history of modern nations and nationalism — basically, nation builders work with materials at hand. [05:50] But at the same time, scholars are often nation builders, and their political commitments shape their scholarship. [05:56]

JMc: And why is genealogy the dominant model for nation building in this period? [06:02] Why is the key thing to trace your nation back to a particular set of ancestors? [06:08]

IS: Basically, I think it’s a pretty simple equation that primacy was really important, so being the first people somewhere, having had, you know, the most extensive territory or the most glorious conquest. [06:25] And so basically, pedigree meant prestige, and we have to remember that before the rise of modern scholarship, you know, before modern historical linguistics, archaeology, folklore I suppose, and things like that, you’re basically working with the classical sources, [06:43] and so if a people is mentioned extensively in the classical sources, like the Celts are, there’s a lot more you can do with that. [06:50]

JMc: So you mentioned that the Celts left behind a certain amount of linguistic evidence. [06:55] How much of a role did this linguistic evidence play in the modern project of constructing Celtic identity, and was it the main kind of evidence, or was archaeological evidence just as important, for example? [07:09]

IS: Things change over time, but I would argue that language has been the most important and consistent thread in tracing the history of the Celts over the last five centuries. [07:20] Basically, linguistics is crucial in the Celtic case for two reasons. [07:26] The first is that it’s only through linguistic scholarship that the entirety of the modern Celtic family was recognized, [07:33] so in other words, that the speakers of the two linguistic branches — so Welsh, Breton, and Cornish speakers — are related to speakers of Irish, Scots Gaelic, and Manx Gaelic. [07:46] And that’s realized about 1700. [07:48] And the second is that it was only through comparative linguistics that the Celtic nations were recognized to be a part of the wider Indo-European family, as opposed to an indigenous population that was pushed further west by invading Romans or Goths, etc. [08:05] And so I can unpack those two things for you. [08:08] On the first point about providing a more holistic picture of the Celts, the interesting thing is that in the early modern period, neither the Welsh nor the Irish, their dominant linguistic tradition isn’t thought to be Celtic, and they actually weren’t thought to be related to each other, and I think this is particularly striking because these are probably now seen as two of the most Celtic nations. [08:32] But basically, native Irish tradition held that the language derived from the ruins of Babel, where the best parts of all languages were cobbled together, and then taken by the Scythians, who became the Scots, to Egypt, Spain, and then Ireland. [08:46] And it’s really complicated, but the point is that it definitely wasn’t Celtic. [08:50] Meanwhile, Welsh tradition held that it derived from Hebrew. [08:54] So before the 18th century, the Celts are sort of most associated with Gaul, and therefore France, and more surprisingly, with Germany. [09:02] So Toon Van Hal has shown how French and German humanists argued over what language Gaulish really was, and which of their modern vernaculars was closest to it, and so the languages of Britain and Ireland aren’t really into the picture. [09:16] It’s more of a Continental argument until about the end of the 17th century, and in fact, no classical sources refer explicitly to the inhabitants of Britain and Ireland as Celts. [09:28] But basically, the important thing that happened was that Caesar had actually described many of the cultural links between Gaul and Britain, and one of those that he’d mentioned was language. [09:37] So as soon as scholars in the early modern period started to get their hands on Welsh vocabularies, they were able to trace links between the few Gaulish words that they had and Welsh, [09:49] and the person who provided the most crucial work was the Dutch scholar Marc van Boxhorn, who recorded that he was so pleased to receive a Welsh dictionary that he kissed it. [09:59] And if the ancient Celts spoke Gaulish, the thinking went, and, according to Caesar, the ancient Britons spoke a similar, if not the same, language as the Gauls, then because Welsh was descended from the language of the ancient Britons, it was probably Celtic too. [10:16] And it was already recognized that Breton and Cornish were related to Welsh, so they all became seen as this cohesive group with likely ties to the ancient Gauls or Celts. [10:26] This is hammered home increasingly towards the end of the 17th century, especially by a Breton monk named Paul-Yves Pezron, who got many things wrong but really succeeded in driving that point home. [10:38] But at this point… [10:39] So in the 1690s, the Brittonic languages and the Gaelic languages were still seen as unrelated. [10:46] The key move here was made by a Welsh scholar named Edward Lhuyd. [10:50] He’s a real hero in Celtic studies. [10:53] He travelled around Britain and Ireland doing fieldwork for several years at the turn of the 18th century, and he actually recorded words from speakers of these languages and drew up vocabularies. [11:06] So in late 1699, he had composed a comparative vocabulary of Welsh, Irish and English words, and there he noted that there were a number of sound correspondences, and the most famous of these is the P and C or Q distinction in Celtic. [11:23] And this is a quote from Lhuyd. [11:24] He said, “I cannot find the Irish have a word purely their own that begins with a P and yet have almost all of ours which they constantly begin with a C.” [11:36] So some of the classic examples of this distinction are pen and ceann (so pen is Welsh for “head,” and ceann is obviously Irish) or pedwar and cathair, which is the number four. [11:50] But it can also be mac, which is the Irish word for “son,” and mab, which is the Welsh word. [11:56] This is now called the P and Q Celtic distinction, and this gave rise to the terrible joke that Celticists have to mind their P’s and Q’s. [12:05] But so it was Lhuyd’s achievement to show that these two branches of language were related and could be referred to as Celtic. [12:16] And so for the second part, connecting the Celts to the Indo-European family, it was comparative philology, obviously, that did this. [12:23] And so after the Celts become established as this cohesive group, there are still lots of opinions flying around in the 18th century. [12:32] We’re still in the era before comparative and historical linguistics became a cohesive discipline with recognized principles and dogmas, really, if you like, [12:42] and actually, some people might have recognized that the Celts were a distinctive family, but they started to doubt whether it was a family that belonged to the larger Indo-European family, because the Celtic languages have some strange features. [12:57] Its vocabulary is quite different. Its grammar also seems strange. [13:02] So, most obviously, it’s a VSO grammatical system, so verb, subject, object. [13:07] It also has, and this is probably the most famous thing, a system of initial mutations where the first sound of a word changes based on its grammatical function in relation to the word before it. [13:18] This can be for grammatical purposes or just euphony. [13:22] And so some people doubted that together these features could be reconciled with the other Indo-European languages, and people like A. W. Schlegel, so no mean philologist, was someone who doubted the position of Celtic. [13:36] And just to make a long story short, in the 1830s, three works were published by the English scholar James Cowles Prichard, by the Genevan Adolph Pictet, and by the German Franz Bopp, who published work explaining these differences and showing how they fit within the European… Indo-European framework. [13:55] Prichard compared Welsh and Sanskrit, Pictet, Gaelic and Sanskrit, and Bopp showed the principles and operation behind the initial mutations, and so these three works together definitively established that the Celtic languages were Indo-European, and therefore that the Celtic race, as it was starting to be called at this time, was part of that larger Indo-European family or race. [14:17]

JMc: So one of the key figures that you mentioned just there was the Englishman James Cowles Prichard. [14:23] So what exactly was his contribution to demonstrating that the Celtic languages are part of the larger Indo-European family, and how exactly did his proof work, and what methods did he use to construct it, [14:37] and did he have any priority over any of the other scholars working at the time on the problem of Celtic as an Indo-European language? [14:46]

IS: That’s a really, really interesting question, one that I’ve worked on for a long time. [14:51] I think he… [14:52] Well, he was someone that was overlooked both in Celtic studies and in the history of Celtic philology, and therefore in the history of Celticism. [15:00] He’s most recognized for having been Europe’s leading ethnologist, so kind of the first phase of anthropology. [15:08] He’s like a physical and cultural anthropologist, but really his largest concern was to ensure that the Celtic nations were — in this instance, his largest concern — was to show that they were part of the Indo-European family for two reasons. [15:23] The first one is biblical orthodoxy. [15:25] He was raised a Quaker, he converted to Anglicanism, but he still obviously adheres to the biblical account. [15:32] And the second reason is that he’s Welsh. [15:34] His mother was descended from a Welsh family, at least is what I think we know, but accounts kind of differ on this. [15:41] Some say that he could speak Welsh with his patients, where he was a physician in Bristol, but it’s clear that he could read Welsh, and he was connected to Welsh cultural circles. [15:50] But the thing that I think that’s most interesting about him in this case is that he was recognizing the sort of the full import both of the Indo-European idea, and of the possibilities for comparative philology, before the major developments in Germany, above all. [16:06] So in 1813, he said that “[i]t’s only an essential affinity in the structure and genius of languages that demonstrates a common origin. [16:15] This sort of relationship exists in the Sanskrit, the ancient Zend, as well as the modern Persic, Greek, Latin, Germanic dialects; and is found, though not to the same extent, in the Celtic and Slavonic.” [16:26] And so basically, what you have there is a pretty clear paraphrase of the philologer passage from William Jones. [16:34] So I think Prichard comes to that as… [16:36] That’s an early conclusion, both in the context of Celtic comparative philology, and I think in the history of comparative philology writ large, but basically, he puts off… [16:47] He says he’s going to publish a work about the Celtic and Slavonic dialects, as he calls them, but he puts this off until 1831. [16:55] He did publish an essay in 1815 where he showed some of these proofs that would appear in his later work, but these were mostly just comparative vocabulary, [17:06] but once you see everything that he puts together, it’s pretty clear that this needs to be explained, and that if it’s not borrowing, you know… [17:17] If it’s borrowing, then there’s a lot of explaining to do, because there is a ton of similarity, but what he eventually does is, he shows some of the grammatical similarities in 1831. [17:28] So he shows that verbs — that’s his main point of evidence — he shows that verbs are conjugated in the Celtic languages in essentially the same way as we’re familiar with in, you know, with the Indo-European languages. [17:40] He shows that verb endings come from abbreviated pronouns, and he’s really riffing off of the work of Franz Bopp here. [17:48] But Prichard was working with modern Welsh, and so he couldn’t really construct a historical grammar in the way that Grimm had for German, but his vocabulary proofs, like I said, are very convincing. [17:59] And Grimm himself announced as soon as he read this work that he had decided… that Prichard had shown this was Indo-European. [18:06] Now, at the same time, Adolph Pictet is working in Geneva on a proof using mainly Irish and Scots Gaelic to show similarities with Sanskrit, and he’s really targeting A. W. Schlegel, and he publishes this proof in a series of three open letters. [18:22] And it’s really funny, Pictet definitely owned Prichard’s work because his copy exists in the Cornell Library, but he never references him, and just over 20 years later, he writes to an Irish scholar who is reviewing a work by Johann Kaspar Zeuss, who wrote the first historical grammar of the Celtic languages. [18:43] This Irish reviewer had written that Zeuss proved the Celtic languages to be Indo-European, and Pictet actually wrote that, “No, no, no, I showed this many years ago, and it’s not fair that you’re saying it was Zeuss.” [18:58] So it’s ironic because Pictet was himself being unfair to Prichard. [19:02] And so, while I think Prichard is recognized to some extent in the 19th century, once we get to the 20th century he’s really written out of the story for reasons that we’re familiar with in the history of linguistics: because as soon as someone’s proof is superseded, they become basically dismissed. [19:21] And so I think part of what I’ve tried to do is recover Prichard both for Celtic studies and for the history of linguistics as part of this sort of new narrative… well, a revision to the standard narrative that you said earlier about what’s happening in the field, and he’s a good example of how approaching the history of the subject in this way can show new things, I think. [19:43]

JMc: So Prichard’s been forgotten in the standard narrative that we tell these days about the history of historical-comparative linguistics. [19:53] How does restoring him to his proper place in this narrative challenge this received story that we usually tell in the history of linguistics? [20:03]

IS: Well, basically, I focus on Prichard because he’s the best linguist out of all the British scholars I’ve worked on, but he actually comes at the end of this line of scholars in Britain who realized the significance of the Indo-European idea well before the sort of German developments. [20:26] And they were all Scots, actually, except for Prichard, though he studied at the University of Edinburgh, and I think that’s really important, because it’s the Edinburgh Review where a lot of this stuff is aired. [20:37] And so this is significant for a couple reasons, one of which is that the history of comparative philology or historical-comparative linguistics in Britain hasn’t really moved on from Hans Aarsleff’s book in 1967, The Study of Language in England, and there, you know, he includes some Scottish developments as part of the English story. [20:59] But so basically, what I’ve tried to do is add Scottish scholars to the picture, and also tried to show that, against Aarsleff’s narrative, that there were people aware of basically the importance of the Indo-European idea, and what comparative philology could do, well before the 1830s, but they were all doing different things with it. [21:21] So Alexander Hamilton, who’s famous for having taught Friedrich Schlegel, he constructed a comparative vocabulary in 1810 in the Edinburgh Review, which Prichard then picked up on, but he was more of a philologist than a comparative philologist, and ultimately, he wrote a really big work on Indian mythology. [21:40] John Leyden was another comparative philologist, but he was far too ambitious, and he was more interested in South Asian and Asian languages, and he died before he could complete anything substantial. [21:51] His friend Alexander Murray completed a big magnum opus, where he clearly recognized the Indo-European idea, and he included the philologer passage, but he was trying to trace the origin of language, which he reduced to nine sounds, which made his book kind of ridiculous at the time. [22:06] But the point is that he was interested in the origin of language and not necessarily the comparison of language for its own sake. [22:13] And all of these guys came before Prichard, who I said had reached this sort of Indo-European recognition by 1813, but his main interest was ethnology. [22:23] And so, what I think I’ve shown is not that British scholars invented comparative philology or anything like that, but basically that they were better than they’ve been getting credit for, and they were interested in many other things, and they died before they could produce anything substantial. [22:38] And British scholars, in this respect, I think, fit into this larger story where, since we’re moving beyond the standard narrative where Jones discovers the Indo-European connection and then it sort of is built from there, [22:52] there’s obviously this revised story that’s developed over the last few decades, like Daniel Droixhe and Toon van Haal are two people who have shown that there was a great deal of what could be called comparative philology going on in early modern Europe. [23:04] Okay, the grammatical aspect wasn’t developed, but the framework is definitely there. [23:09] And our friend Floris Solleveld has been rewriting the history of linguistics in the 19th century and showing how that similar ideas that we think of with the Indo-European family were being developed in relation to families like the Malayo-Polynesian group. [23:25] But Floris has really shown also just how difficult it was to get linguistic samples, and that scholars actually had to have the material with which to work. [23:36] And so, if you read Wilhelm von Humboldt or Peter Stephen Du Ponceau, two early 19th-century linguists, they weren’t talking about the philologer passage. [23:45] They were praising, you know, Adelung and Vater and the Mithridates, you know, for bringing much more linguistic evidence beyond Europe to light, and Prichard actually also reviewed the Mithridates, and that’s where he lays out his idea of the Indo-European idea fairly early. [24:03] And so with this… the revised standard narrative is part of realizing that people were using language and linguistic studies for things far beyond just, you know, the intrinsic language of… language itself. [24:16] I think it should help us to realize that language was… is, was and has always been, you know, a central point of consideration in definitely the Western intellectual tradition from the ancient period onwards. [24:31] So I think it’s, you know, it’s helpful for us to realize that with the study of language, we can learn a lot more about the human sciences and the humanities, and I think also that the humanities and human sciences, social sciences, have a lot to learn by considering the history of linguistics. [24:46]

JMc: Great. Well, thank you very much for answering those questions. [24:50]

IS: Yeah, thanks. Thanks. Thanks for having me, James. [24:52]

Podcast episode 43: Judy Kaplan on universals

In this interview, we talk to Judy Kaplan about universals in American linguistics of the mid-20th century.

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | YouTube

References for Episode 43

Emmon Bach & Robert T. Harms, Universals in Linguistic Theory (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968)

Noam Chomsky, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1965).

Jamie Cohen-Cole, The Open Mind: Cold War Politics and the Sciences of Human Nature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Joseph Greenberg, “Some Universals of Grammar with Special Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements,” in Idem (ed.), Universals of Language (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1963), 73-113.

______ “The Nature and Uses of Linguistic Typologies,” IJAL 23: 68-77.

Roman Jakobson, Kindersprache, Aphasie und allgemeine Lautgesetze. (Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksell, 1941).

Linguistic Society of America, Committee on Endangered Languages and their Preservation, “The Need for the Documentation of Linguistic Diversity,” June 1994. (https://old.linguisticsociety.org/sites/default/files/lsa-stmt-documentation-linguistic-diversity.pdf)

Janet Martin-Nielsen, “A Forgotten Social Science? Creating a Place for Linguistics in the Historical Dialogue,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 47(2): 147-172.

Transcript by Luca Dinu

JMc: Hi, I’m James McElvenny, [00:09] and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences podcast, [00:13] online at hiphilangsci.net. [00:16] There you can find links and references to all the literature we discuss. [00:20] Today, we’re talking to Judy Kaplan, who’s a historian of the human sciences and a Curatorial Fellow at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia. [00:30] One of Judy’s current projects is to investigate the notion of universals in American linguistics of the mid-20th century. [00:39] Why is it that various competing schools of American linguists in this period converged [00:44] on universals as the target of their research, despite their fundamental differences in scientific outlook? [00:50] What did they mean by “universals”, and what role did universals serve in their respective theories? [00:57] So, Judy, can you sketch the scene for us? [01:01] What was happening in American linguistics in the mid-20th century? [01:04] Who were the leading figures, and what positions did they take? [01:09]

JK: Thanks so much. [01:10] Viewed from above, we can see that the mid-20th century was a time of remarkable growth and expansion in American linguistics, [01:18] so funding went up, the first university departments were established, and the ranks generally grew. [01:25] These markers corresponded to a handful of different programs or positions. [01:30] As far as those leading figures and positions, most people concentrate on two dominant approaches to the study of language at this time: structuralism and generative grammar. [01:42] I should say that both were internally heterogeneous. [01:46] On the structuralist side, there were students of Edward Sapir in the anthropological tradition and Leonard Bloomfield on the more strictly linguistic side. [01:54] Structuralists focused on speech, a sort of self-conscious departure from 19th-century philology, on form, [02:01] on abstractions — ultimately, as the name suggests, on structure. [02:06] In terms of evidence, they were heavily invested in the study of Native American languages. [02:12] By the post-war period, the so-called neo-Bloomfieldians or distributionalists were at centre stage. [02:19] So, figures here are people like Charles Hockett, Zellig Harris, Bernard Bloch, Martin Joos, and others. [02:26] To your question, their position was basically that linguists should be looking at how linguistic forms show up in different speech environments. [02:33] They insisted on the distinction of different levels of analysis — so, phonology, morphology, syntax, these were all different levels. [02:40] And these points of emphasis pretty much bracketed meaning and the mind, which is important. [02:47] Much of the work was really mathematical in terms of its look and feel. [02:51] Emerging in a sense from this tradition, but also deeply critical of it, was Noam Chomsky and the study of transformational grammar. [02:58] This program elaborated transformational rules, and that was a term that was adapted from Harris, so you can see that there’s this kind of emergence. [03:06] So, it elaborated these transformational rules to link fundamental deep structures of language to surface manifestations, allowing linguists to turn from empirical data toward the study of grammar and the mind. [03:19] The emphasis was on theory construction, evidence of linguistic competence, and the definition of rules. [03:25] Though this program subsequently splintered into groups dedicated primarily to syntax and semantics, it did come to define a new mainstream. [03:35]

JMc: So, how do universals fit into this picture? [03:39]

JK: In a very broad sense, I think universals trace back to the supposed liberation of linguistics from philology — the question being, was linguistics going to be about language or languages? [03:49] So, if the former, then one might reasonably be on the lookout, at the end of the day, for features or phenomena that are universal in scope. [03:59] Just circling back then to the general lay of the land, it’s interesting that historians of science — so I come out of history of science — that they have tended to write about this with different points of emphasis, as opposed to linguistic historiographers or historians of linguistics, first and foremost. [04:16] Historians of science have characterized the relationship between these two approaches (the structuralist and the generative) as the contrast between behaviourism and mentalism, which was given all sorts of ideological overtones in the post-war period. [04:31] Linguists writing about their own history have wrestled with whether or not the remarkably swift emergence of transformational grammar constituted a scientific revolution in the Kuhnian sense. [04:42] It was unquestionably a remarkable turn, so participant accounts, institutional changes, interdisciplinary engagements, and citation patterns all make that really clear, [04:52] but there were also many linguists who were already trained and working in the structuralist tradition who felt that transformational grammar was not really for them. [05:01] And I might locate Joseph Greenberg somewhere in there, right? [05:05] So he was coming out of anthropology, first and foremost, he received his PhD in anthropology, and became really well-known by the 1950s for working on the genetic classification of African languages. [05:19] He was quite well regarded for that work. [05:22] He first turned to the study of African languages because he had been interested in Arabic and Semitic and had been approaching these from an anthropological standpoint, [05:31] and in 1957, he started to write about typology, and typology in connection to universals. [05:38] So Greenberg is taking a typological approach to the study of language universals, and he is leaning pretty heavily on the work of Roman Jakobson, who had introduced them in connection to the acquisition of child language. [05:52] One of the things that he says here is that it’s really important to consider implicational universals, so of the form “if X, then Y,” [05:59] and he sets out on a kind of data-gathering mission with this in mind. [06:04] And, you know, when he tees up the program — this was launched in a 1961 conference at Dobbs Ferry — [06:11] when he tees up the program, he says, you know, We have accumulated so much data at this point in time that the time is ripe to turn to the study of language universals. [06:22] Coming back to the question about how universals fit into the general topography or the landscape of post-World War II American linguistics, historians of the human sciences have shown how, in the wake of World War II [06:38] — which, you know, perpetrated unprecedented violence based on these racist and eugenic ideas that some human groups were distinct and less valuable than others — [06:47] liberal biologists and anthropologists, also psychologists, also I would add linguists here, came together to try to define a rosier and more inclusive picture of human nature. [06:59] So this was a picture that celebrated our best features as humans, our intelligence, our technological prowess, our cooperation, and also our common inheritance. [07:11] So I think that this is really important for understanding why this turned to universals in the mid-20th century. [07:17] That said, the way that Greenberg and Chomsky defined and operationalized universals research could not have been more different. [07:26] So Greenberg edged up to the study of universals defined in this typological way in a 1957 paper for the International Journal of American Linguistics. [07:36] This previewed his 1961 contribution to the Conference on Language Universals at Dobbs Ferry, “Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful events.” [07:46] This became known as the word order paper. [07:49] It’s really important and sort of set the agenda for this approach to the study of universals. [07:55] It gives a clear sense of what this research program was going to be all about. [07:59] It talked about things like sampling procedures, empirical evidence, the typology of word order of course, and it also offered some thoughts on the relationship between linguistics and other human sciences. [08:11] It was guided by the idea that the best, and you could say really the only, way to study universals was inductively. [08:19] So I mentioned before a debt that Greenberg had to Roman Jakobson, this idea of implicational universals, which appears I think in the first paragraph of that paper. [08:29] And so this, again, is this idea of “If you have this feature, you’re also going to have this feature,” or, you know, there’s going to be some other kind of constraint. [08:36] And this is just to point out maybe something that people haven’t necessarily thought about. [08:40] This is really a different way of saying what is commonly held as opposed to a statement like “All languages have Z.” [08:49] I think it’s also important to say something about the social organization of Greenberg’s research program. [08:56] As this was an effort to coordinate empirical generalizations on a massive scale, an army of researchers was needed. [09:03] They also needed to think carefully about how to manage their data, [09:06] so he was invested in the creation of some sort of cross-cultural file, he called it. [09:12] Greenberg said that coordinated efforts beyond the scope of individual researchers were going to be necessary to establish on firm grounds the actual facts concerning universals and language. [09:23]

JMc: So do you think this inductive approach of Greenberg is an example of this contrast that linguists often make between, you know, empiricism and rationalism in their approach to linguistics? [09:34] I mean, the generativists love to talk about that. [09:37]

JK: Yes, I think it’s important to differentiate between empiricism as a theory of mind and empirical research methods. [09:45] Mostly what I’ve been talking about here are empirical research methods and rationalism versus a sort of logical way of going about doing things. [09:54] So just to differentiate between the theory of mind and the methodology is important. [10:00] But yes, these do sort of map onto those basic traditions. [10:05]

JMc: Do you think it’d be fair to say that it’s part of generativist propaganda to conflate these two things and to set up this opposition? [10:13]

JK: Yeah, probably. [laughs] [10:15] I mean, I think the rationalist, in the sense of a theory of mind, description, applies to Chomsky. [10:22] It’s just that the empiricism, empirical method doesn’t necessarily apply to Greenberg. [10:28] But if you are in the generativist camp and you’re looking at what the linguists who are using empirical methods are trying to do, yeah, to sort of suggest that conflation does important work, [10:40] because it maybe consigns everyone who’s looking at actual attested language data to maybe this behaviourist tradition, which by the mid-20th century was sort of much maligned. [10:52]

JMc: How does Chomsky then fit into this picture? [10:53] So you’ve mentioned Greenberg. So did Greenberg start talking about universals and Chomsky sort of tried to catch up to him? [11:01]

JK: They both arguably were publishing on universals in 1957, [11:06] so there’s a real kind of direct coincidence here. The- [11:10]

JMc: And they both use the term “universals.” [11:12]

JK: Not exactly. So Chomsky uses it a little bit later. But the universals that Chomsky and his colleagues were interested in, [11:19] so this is on the other hand, they didn’t pertain to languages so much as they had to do with those internal aspects of linguistic theory that might be then regarded as universal [11:31] — so, for instance, the very idea that transformational rules can get you from meaning to sound via the grammar. [11:39] If these could be established, then these would call for some kind of further explanation, and this ends up being a claim about innateness, which is sort of characterized as a biological endowment. [11:51] Chomsky started talking about universals in an explicit way, to your question, in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. [11:58] Here he links linguistic universals to the idea of explanatory adequacy and draws a really bright line between formal universals, that’s what he’s going to be interested in, and substantive universals, and this is more of the Jakobson-Greenberg cast. [12:14]

JMc: Okay, so does “formal universals” mean universals pertaining to theory construction about what linguistic grammars look like, whereas substantive universals are empirical findings about the structures of actual languages? [12:30]

JK: Exactly. He says early on in that text that “the main task of linguistic theory must be to develop an account of linguistic universals”, so this is a pretty clear statement, [12:41] and he urges that this account needs to be able to stand up to the actual diversity of human languages, while at the same time also accounting for the rapidity and the uniformity of language learning in rich and explicit ways. [12:53] So here he’s gesturing again to that kind of species-level endowment. [12:59] He gives examples of reducing or absorbing, I think he uses the word “abstracting”, phonological rules in English. [13:08] So here’s a, you know, what might be considered a substantive universal in the way that you just described, to the formal universal that a transformational cycle universally links phonological rules to syntactic structure. [13:22] And then this would have the advantage of explaining away funny-looking exceptions in terms of deeper underlying regularities. [13:31] If you look at the papers that were presented at the conference that was held on universals of linguistic theory… [13:36] So I’ve been thinking about these camps in terms of two organizing conferences. [13:40] So there was the one in Dobbs Ferry in 1961, and this other conference that was held, actually weirdly, on the same day, but just a few years later. [13:50] It was held, I should say, at UT Austin. [13:53] The kinds of universals, just to give a feel again, the kinds of universals that were up for discussion were very general things like case and modality. [14:03] They were derived primarily from common-sense intuition. [14:06] So if you contrast that again with the kind of empirical way in which Greenberg was working, they were mostly offered up by native speakers and they were mostly having to do with English language usage. [14:16]

JMc: So common-sense intuition, you mean these intuitions about grammaticality judgments? [14:21]

JK: Exactly. [14:22]

JMc: So whether you can say this or not, and put a star in front of it if you can’t. [14:25]

JK: Exactly.

JMc: Yeah, OK. [14:27]

JK: Yeah, and just to give one example of that, in his contribution to the conference, Paul Kiparsky suggested that rule addition and rule simplification might be called or considered universal processes of human language. [14:39] So you can get a sense of the feel that these are very, very different approaches. [14:42]

JMc: Yeah. OK. [14:44]

JK: The introduction to the proceedings that was published from that conference mentions that it was all tape recorded, and I’ve been trying to find the tapes [laughs] because, you know, yeah, the generativists are known for having these really rowdy conferences, [14:59] and I really want to hear what was actually said, but I haven’t been able to find them. [15:02] So if anybody listening knows where to find those tapes, please let me know. [15:06]

JMc: OK. So these two conferences, Dobbs Ferry and then UT Austin, who were the participants in these conferences? [15:15] So like, what was the sort of character of them? [15:18] So was the Dobbs Ferry conference more anthropological in orientation? [15:22]

JK: Yeah, so the Dobbs Ferry conference was funded by the SSRC, so the Social Science Research Council. [15:28] It grew out of conversations that were happening during… I want to say the academic year of 1958–59 at Stanford. [15:35] And, you know, as it’s described in the notes, there’s this sense that psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and linguists all needed to be talking about kind of universal phenomena. [15:48] So in terms of the participants at Dobbs Ferry, it was a very interdisciplinary group. [15:53] I think Greenberg says at one point that if we edge up to the universal, we’re going to go over this tipping point into psychology and anthropology. [16:02] As for UT Austin, Emmon Bach was there, Paul Kiparsky, I’m going to forget other names. [16:08] But just, you know, this was largely drawing on a pretty intimate group of actors in the transformational-generative school. [16:16]

JMc: And Greenberg’s statement about if we, you know, keep pursuing universals, we’ll end up doing psychology, is that intended as a reductive statement? [16:24]

JK: I don’t think so. [16:26] You know, again, he was really keen to work in an inductive way, so to amass a long list of generalizations, to take a step back from those to maybe elaborate even deeper fundamental principles, at which point you would be thinking you would have to confront psychology, [16:43] I think that’s more the spirit of in which he’s talking about this interdisciplinary engagement. [16:47]

JMc: You’ve sort of already touched on this idea when you mentioned that there was a movement among liberal scientists in America after the war to try and claw back some notion of our common humanity after the horrors of World War II, [16:59] but could you say a little bit more about why this idea of universals and this term “universal” was such a powerful concept for linguists? [17:08] And this was true of the broader social sciences, I take it, and even biology and medicine? [17:16]

JK: Yeah, well, focusing on linguistics for a second, I see the move towards universals, and both empirical and formal here, as an expression of sort of extraordinary disciplinary self-confidence in the middle of the 20th century. [17:27] So I talked at the beginning about how the discipline was on the rise, basically, and I think you have to be in that sort of powerful position to be able to take on or attempt to tackle something as ambitious as the universal. [17:39] It reminds me actually of the way that professional historians have sometimes put down antiquarian traditions. [17:45] So yeah, so just to say “We’re not going to look at these narrow phenomena; we’re going to look at something really ambitious and broad.” [17:52] In the writings of both Greenberg and Chomsky, you get the sense that describing the idiosyncrasies of language can be interesting, but that this is somehow too quaint. [18:01] So to come back to this idea of self-confidence, Greenberg says in his introduction to the Dobbs Ferry volume, and I’m paraphrasing here, that synchronic and diachronic linguistics has achieved sort of a high level of methodological sophistication, [18:15] and that also — and I think this is really important — that it has amassed a huge amount of data, such that the time was going to be really ripe for generalizing on a wide scale. [18:26] Chomsky says something similar, which is that traditional and structuralist grammars have provided extensive lists of exceptions and irregularities, but for him that meant that it was time to start moving beyond these to talk about underlying regularities. [18:40]

JMc: So how does this notion of universals — and the term “universal”, you know, which as you have just demonstrated, is actually being used in very different ways by people like Chomsky and Greenberg — how does this fit into what the broader human sciences were doing? [18:56]

JK: Other human sciences were talking about human nature, so I think that that’s where the point of connection is. [19:01] I haven’t necessarily seen universals as a term of art in other disciplines, but I think it’s really important to note — just with respect to this relationship between linguistics and the other social sciences, where it fit into the picture — it’s really important to note that linguistics was very successful. [19:19] It was really attractive to the folks, say, at the NSF who were holding the purse strings after World War II. [19:26] So the National Science Foundation, it might be helpful to clarify here, it made awards to both Chomsky and Greenberg. [19:34] So clearly this term, “universals”, was attractive to folks who had control of the money. [19:43]

JMc: So why did the NSF like linguistics so much? Was it because linguistics has the appearance, you know, with its sort of mathematization of grammar, has the appearance of a hard science, like of a real natural science, or could it be something else? [19:58]

JK: [laughs] That’s very intriguing. [20:00]

JMc: [laughs] [20:01]

JK: So… Right, so when the National Science Foundation was first established, it was not going to touch the human sciences. [20:08] It was not going to touch the social sciences at all. [20:11] It was established specifically for the physical sciences and engineering disciplines like this, [20:15] and so that’s how linguistics kind of snuck in, and with it, all of the social sciences. [20:22] So the first award that was ever made by the NSF to a project in the social sciences went to Chomsky, in fact, and the Research Laboratory of Electronics at MIT. [20:33] This was in 1956. [20:35] And, you know, it came as part of an initiative to support computation centres and initiatives and research having to do with numerical analysis. [20:45]

JMc: But did the NSF describe Chomsky’s project, like did they categorize Chomsky’s project as social sciences or as engineering? [20:53] Because, I mean, it’s in the research lab for electronics. [20:56]

JK: Yeah, as a computational initiative. [20:58]

JMc: Yeah. OK, so the NSF didn’t think of it as social sciences at all. [21:02]

JK: No, but it set up this precedent. [21:04] So the NSF was interested in funding linguistics because it was associated with computation and mathematics, and, you know, this set up a precedent where an emphasis on formalism and connections to engineering and the natural sciences — also, machine translation — were really, really at the top of the list of priorities. [21:25]

JMc: OK. So this sort of actually ties into a recent interview that we had with Chris Knight, you know, and Chris Knight, of course, has formulated the thesis that Chomsky, you know, deliberately made his work in generative grammar so abstruse so that it couldn’t be used in practice. [21:43] But he was being… Chomsky was being funded precisely because it could have practical engineering applications. [21:50]

JK: Yeah. Computer scientists saw a great deal of promise in what Chomsky had to offer, but he pretty quickly turned against computational projects, which is interesting. [22:03]

JMc: So, I mean, there’s this mathematization and possible applicability of linguistics [22:08] or possible engineering applications of linguistics, but are there any other features of linguistics as a discipline, as a social science discipline, that made it attractive to funders? [22:19] Perhaps the fact that it was, you know, so abstract and, you know, and mechanical? [22:26]

JK: Yeah, I think that’s really important. [22:29] As these federal funding agencies for scientific research were first getting set up, there was a desire to not be too overtly political, so the very, very abstract nature of linguistic research, and particularly, I would say, research on language universals, it fit the bill, [22:47] whereas projects in sociology or anthropology could have direct relevance to what was going on in the Cold War, say. [22:57] So there is something that was highly attractive about the really abstract nature of linguistic research. [23:03] I think… I’ve looked at correspondence from the Ford Foundation, and, you know, you have these sort of these program officers who are writing back and forth, trying to explain to each other what the linguists are doing, and they have a really tough job of it, and I think that’s actually really productive [laughs] for the field. [23:21] Another thing to say here is that in 1958, there was a really important piece of legislation that was passed, the National Defense Education Act, [23:29] and this is all, you know, sort of the history of big science. [23:34] And historians of science have really emphasized the way in which this led to, you know, expanded educational initiatives and funding for science and technology. [23:45] The piece that is often left out of that conversation is that it also sent a lot of money toward linguistics and linguistic training. [23:53] So the idea was that Americans had not bothered to learn other languages, and in the effort to sort of persuade international actors to join up with the American cause, that it’d be really, really helpful to actually be able to communicate. [24:13] And, you know, that might seem like a very practical goal, but there was a lot of research into how people actually learn languages and how this can be facilitated that was very abstract and basic and fundamental in nature. [24:26]

JMc: Was this discussion of universals a contained episode in the history of linguistics? [24:32] Did this universals discourse die down, or has it morphed into something else in contemporary linguistics? [24:39]

JK: I don’t know about contained, but I do think that the 1960s and early 1970s were a high watermark in the study of language universals. [24:48] You can see this… You know, so basically the argument that I’m trying to make with this research project is that if we think of linguistics as centrally having to do with this tension between the diversity of human languages and language as a species-defining function, or faculty I should say, those things are always in tension, but at the same time, when you look across time, I think that they sort of ebb and flow in terms of priority and succession. [25:14] You know, early 20th century before World War II, say, in American linguistics, this is a period that’s really defined by particularist interests in language. [25:23] By the time you get to Greenberg and Chomsky, it’s very, to use the word “universal”, universalist, [25:31] and, you know, following that time, there’s a return to a primary commitment to the particulars of human language, [25:39] and, you know, this gets bound up with concerns about linguistic diversity and the documentation of linguistic diversity. [25:47] One of my favourite sources on this is the 1994 statement on “The Need for the Documentation of Linguistic Diversity” that was put out by the Linguistic Society of America, and there, you could see that they’re looking back on this period in the 1960s and ’70s, and, you know, maybe even edging into the ’80s to some degree, although it gets messy, where typological research and generative research are really, you know, at the top of the discipline’s priorities. [26:15] And I think that that’s really interesting. [26:17] And so in this statement, you know, there’s this sense that these kinds of research programs (so the typological, the generative) need to somehow be folded into and inform a return to a primary interest or commitment to linguistic diversity. [26:35] So that tells me that this is a period that’s coming to an end. [26:38] It was unique. [26:39] It was bounded in some sense. [26:41] But yeah, that nevertheless, these were really, really important projects at the time. [26:46]

JMc: Well, thanks very much for answering those questions. [26:49]

JK: Sure.

Podcast episode 42: Randy Harris on the Linguistics Wars

In this interview, we talk to Randy Harris about the controversies surrounding the generative semantics movement in American linguistics of the 1960s and 70s.

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | YouTube

References for Episode 42

Chomsky, N. (2015/1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax (50th Anniversary edition.). The MIT Press.

Harris, R. A. (2021/1993). The linguistics wars: Noam Chomsky, George Lakoff, and the battle over Deep Structure (2nd ed.). Oxford.

Huck, G. J., & Goldsmith, J. A. (1995). Ideology and linguistic theory: Noam Chomsky and the deep structure debates. Routledge.

Katz, J. J., & Postal, P. M. (1964). An integrated theory of linguistic descriptions. M.I.T. Press.

McCawley, J. D. (1980). Linguistic theory in America: The first quarter-century of transformational generative grammar, by Frederick J. Newmeyer (Book Review). Linguistics, 18(9), 911-930.

Newmeyer, F. J. (1986/1980). Linguistic theory in America: The first quarter-century of transformational generative grammar (2nd ed.). Academic Press.

Postal, P. M. (1972). The best theory. In S. Peters (Ed.), Goals of linguistic theory. Prentice-Hall.

Postal, P. M. (1988). Topic…Comment: Advances in linguistic rhetoric. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 6(1), 129–137.

Transcript by Luca Dinu

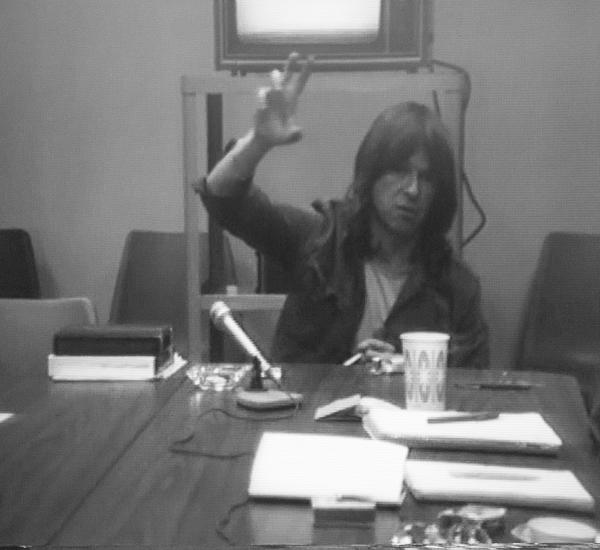

JMc: Hi, I’m James McElvenny, and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences podcast, [00:14] online at hiphilangsci.net. [00:17] There you can find links and references to all the literature we discuss. [00:21] Today we’re talking to Randy Harris, [00:24] who is Professor of both English Language and Literature and Computer Science at the University of Waterloo in Canada. [00:32] Among other things, Randy is the author of The Linguistics Wars, [00:37] the classic account of the generative semantics controversy that engulfed generative linguistics in the 1960s and ’70s. [00:45] A second edition of Randy’s book came out in 2021, and I’ve been wanting to talk to him about it since then, [00:52] but as a history podcast, we are by definition behind the times, [00:57] so it’s only appropriate that we’re only getting to his book now. [01:01] So, Randy, can you tell us, what were the linguistics wars? [01:05] Who were the chief combatants, and what were they fighting about? [01:09]

RH: Well, first, thanks for inviting me on. I’m a big fan of the podcast. [01:13] It’s a really important and interesting podcast about the history of linguistics, [01:18] and I’m also a fan of your work, your Ogden book, Language and Meaning. [01:22] It is really, really valuable, and I’m looking forward to the new one that you’ve got coming out on the history of modern linguistics. [01:30] So, maybe the best way to start is just to talk about how I entered the project in the first place. [01:35] So, I was a PhD student, and I just discovered a field called rhetoric. [01:41] My other degrees were in literature and linguistics before I got there, [01:46] and I was casting around. I’d originally gone to do communication theory, [01:50] but it turned out that the department wasn’t as strong in that as I thought, [01:54] and they had a really good rhetorician, and he was doing something called rhetoric of science, [01:59] which is basically the study of scientific argumentation. [02:03] I started reading in that field quite a bit and studying under him, Michael Halloran, [02:08] and then when it came time to write a dissertation, I started casting around for scientific episodes. [02:14] One of the themes of rhetoric of science at that point was mostly looking at controversies, [02:19] looking at how scientific disputes get resolved or fail to get resolved through warring camps. [02:25] I read Fritz Newmeyer’s book, Linguistic Theory in America, [02:29] and one of the key chapters is about this group called the generative semanticists and Chomsky coming at odds with each other, [02:39] but I’d also read a review of the book by James McCawley, [02:42] who was one of the people associated with the linguistics wars on the generative semanticists’ side, [02:47] and it was fairly polite, but said that basically Newmeyer’s book didn’t tell the whole story. [02:53] So I thought, “Well, I’d look into this a bit,” and I wrote basically all of the major players. [02:58] So I wrote Chomsky, of course, and the major players on the generative semanticists’ side were Paul Postal, [03:06] who was a colleague of Chomsky’s just before that, George Lakoff, John Robert Ross (Haj Ross), [03:13] and Ray Jackendoff, who was aligned with Chomsky in this dispute, [03:17] but also a lot of people around the dispute [03:21] — Jerrold Katz, Jerry Fodor, Thomas Bever, Arnold Zwicky, Jay Keyser, Robert Lees, Morris Halle, Jerry Sadock, Howard Lasnik, [03:30] just everybody who had seemed to have something to say about that dispute and about the theories around them — [03:37] and I got just an overwhelming response. [03:40] Everybody wanted to talk about it. [03:43] I can’t remember the exact order in which it happened, whether it was a response to a letter that invited me to call or a phone call as a response to my initial letter to Lakoff, [03:52] but Lakoff and I were on the phone for like an hour and a half one night, [03:56] him just going through what everything was all about. [03:59] So this was 20 years after the dispute, more or less, and everybody was still wanting to talk about it. [04:06] There were still hurt feelings and incensed attitudes and so forth, [04:10] and I was coming at it from a completely different discipline and a PhD student, [04:16] not anybody really in the field, and all of them wanted to talk to me. [04:20] So it grew into a kind of oral history project. [04:22] I travelled around and interviewed them all. [04:25] I ended up with like 500-some-odd pages of transcripts of interviews. [04:29] I met Lakoff in a bar in Cambridge. I talked to Chomsky for hours in his office. [04:35] I went to the University of Chicago, and one of the sociological centre points of the generative semanticist side was the University of Chicago, [04:42] especially all of the conferences and publications out of the Chicago Linguistic Society, [04:47] and talked to McCawley and Sadock and so forth there. [04:50] So everybody wanted to talk about it. [04:52] It was a really interesting story. [04:54] What was it? I’ll give you the scientific development story first. [04:58] So Noam Chomsky and his collaborators, most prominently Paul Postal and Gerald Katz, [05:06] developed a theory coalesced in the book Aspects of the Theory of Syntax in 1965 [05:12] that had this central notion of deep structure. [05:16] The model itself was structured as a process model where you generate sentences, [05:22] and it was a sentence grammar, not an utterance grammar. [05:25] All of the proponents denied that it was a process. [05:28] They just talked about it as an abstract model of linguistic knowledge in some way, [05:32] but it was shaped as a process model in which you had a set of syntactic rules, [05:37] phrase structure rules, that generated a syntactic structure [05:41] and a bag of words, a dictionary, a lexicon, that then populated the structure. [05:48] And then what you got was the deep structure, which wasn’t what we speak with [05:55] or write with, but an underlying representation that somehow crystallized [06:00] essential aspects of how we speak, one of them being semantic. [06:05] So a paradigm case would be the passive transformation. [06:09] The phrase structure rules and lexicon give you something like [06:13] “John walked the dog,” and that might percolate through with a few adjustments [06:18] in terms of morphology and then percolate through to the surface structure, [06:22] which was a much closer representation to how we talked, [06:25] or it might go through a passive transformation and come out as [06:28] “The dog was walked by John.” [06:31] The arguments around that focused on the fact that both “John walked the dog” [06:36] and “The dog was walked by John” have essentially the same semantics, [06:40] the same role, the same walker and walkee, agent and patient. [06:45] And so the claim developed that transformations don’t change meaning, [06:51] that meaning resides in the deep structure. [06:55] That’s the 1965 Aspects case. [06:58] So several linguists — most notably Lakoff, Ross, and Postal — [07:06] started enriching the semantics of deep structure, [07:10] making it more and more semantically responsible until it effectively became, [07:15] for the generative semanticist, the semantic representation. [07:18] The Aspects model had a set of semantic interpretation rules that looked [07:23] at the deep structure and found out what the meaning was, [07:26] but the generative semanticists said that the semantic representation was deep structure, effectively. [07:31]

JMc: So what exactly is a semantic representation in this model? [07:34] Is it propositional semantics only, or does it include even details of what we would now consider pragmatics? [07:42]

RH: Well, still in the immediate aftermath of Aspects, just propositional semantics entirely, [07:49] but the argument started to coalesce around dismantling deep structure. [07:54] So one set of arguments around the verb “kill,” for instance. [07:58] “Kill” could be seen as “cause to die.” [08:01] “Cause to die” could be seen as… or “die” could be seen as “not alive,” [08:05] and so “kill” could be seen as “cause to be not alive.” [08:10] And then in the generative semanticist approach, [08:13] these were assembled into the surface structure, assembled in bits and pieces. [08:19] So things like “cause,” “not,” “alive,” were all semantic primitives, [08:25] semantic predicates in and of themselves that got assembled [08:27] into the words that we spoke with. [08:30] And if that’s the case, you can’t have a level of deep structure that inherits words. [08:36] It’s building words. [08:38]

JMc: And can I just quickly ask, what was the nature of these semantic primitives? [08:42] Are they like what Wierzbicka was talking about in the ’70s? [08:47]